- Local Survivor registry

- EDITH LUCAS PAGELSON

- Local Survivor registry

- EDITH LUCAS PAGELSON

Survivor Profile

EDITH

LUCAS

PAGELSON

(1926 - 2023)

PRE-WAR NAME:

EDITH HERZ

EDITH HERZ

PLACE OF BIRTH:

WORMS/RHEIN, GERMANY

WORMS/RHEIN, GERMANY

DATE OF BIRTH:

SEPTEMBER 20, 1926

SEPTEMBER 20, 1926

LOCATION(s) BEFORE THE WAR:

WORMS, GERMANY; DUISBURG, GERMANY

WORMS, GERMANY; DUISBURG, GERMANY

LOCATION(s) DURING THE WAR:

TEREZIN; AUSCHWITZ II, BIRKENAU; STUTTHOF LABOR CAMPS

TEREZIN; AUSCHWITZ II, BIRKENAU; STUTTHOF LABOR CAMPS

STATUS:

SURVIVOR

SURVIVOR

RELATED PERSON(S):

HENRY LUCAS - Spouse (Deceased),

ARTHUR PAGELSON - Spouse (Deceased),

FLORA HERZ - Mother (Deceased),

ALBERT HERZ - Father (Deceased),

SUSE ROSENSTOCK, sister (Deceased),

RUTH LUCAS FINEGOLD - Daughter,

JERRY ALLAN LUCAS - Son,

JACOB LUCAS - Grandson,

HANNAH FINEGOLD - Granddaughter

-

EXTENDED BIOGRAPHY BY NANCY GORRELL

Adapted from Edith Lucas Pagelson, Against All Odds: A Miracle of Holocaust Survival

Edith was born on September 20, 1926 in Worms, Germany to Flora and Albert Herz who owned and operated a retail and wholesale hardware business. Worms is located on the west bank of the Rhine River and had a rich history as a center for Judaism since the Middle Ages, when Worms was the home of the great scholar, Rashi. The Rashi synagogue was desecrated on Kristallnacht and later destroyed by World War II bombing. The Jewish community was completely extinguished and scattered.

For the first eight years of Edith’s life, 1926-1934, according to her, “life was normal.” They were a family of four: mother, father, sister and little sister, Suse, four years younger (Refer to Suse Rosenstock’s Survivor Registry). They lived in a “nice apartment,” her parents made a good living and they were comfortable. Edith and Suse shared a room and slept together. When Edith was nine, she took care of Suse. Edith went to a local public school. She had lots of friends. “They came to my house; I went to theirs. There was no distinction between Jews and non-Jews.” Edith’s parents were religious with an active Jewish life. The belonged to synagogue and went there regularly.

All that changed after November 10, 1938. Edith was 12 years old; it was Thursday. Her father came home from the synagogue, just as he had done each day to say Kaddish for her grandparents who had passed away earlier in the year. He said, “You don’t have to go to school today; they burned the synagogue.” According to Edith, in one night,1,350 synagogues were burned to the ground; 91 Jews were killed; 30,000 Jews were thrown into concentration camps; 7,000 Jewish businesses were destroyed; and thousand of Jewish homes were ransacked. “Life as I knew it was going to change forever.”

Some Jews in Worms opted for emigration abroad. Edith’s parents weren’t among them because her mother’s parents were still alive. By the end of 1935, while 25% of Jews in Worms emigrated, Edith was not allowed to attend public school. Her father’s business was stormed by the SA troopers. Eighty-seven male Jews in Worms were arrested. Edith’s father fled into the woods only to be arrested upon return and sent to Buchenwald. Flora went daily to the Gestapo office pleading for her husband’s release based on his WWI Iron Cross award. After six weeks, Albert came home. Edith recalls, “I hardly recognized him, he aged 10 years. He came back a broken man, but never talked about it.”

The Herz family now had to make critical decisions about their survival. Edith’s parents talked about the Kindertransport for their children. They were able to get Suse, at age eight, on the Transport to Coventry, England where she was welcomed by the Perry family as a foster child. There was a similar but smaller effort to the United States for about 1,000 Jewish children. Edith’s parents waited for the final papers for Edith to travel to Cincinnati, Ohio. Her bags were packed, but the papers never came. Her father suspected that another family made a bribe and got her spot. According to Edith, “No other opportunity presented itself in large part due to the American government’s shameful refuge policy.” In February 1939, Senators Robert Wagner and Edith Rogers sponsored a bill that would have granted permission for 20,000 German Jewish children under the age of 14 to come to the U.S. It was blocked by the Isolationists and not supported by FDR and the bill died in committee. The Herz family moved to Duisburg where they had family at the beginning of 1939. Transport cars began leaving for the East but they remained in Duisburg with about 1,000 Jews. In 1941, the second transport left with Horst Lucas who would become Edith’s husband. Her parents continued to try to get visas for emigration to no avail. The Kindertransport was no option by that point.

Their luck came to an end on July 26, 1942, when they reported to the station for deportation to Theresienstadt. They did not know where they were going, just that they were going East, passing through Austerlitz, Sudentenland, and Czechoslovakia. When Edith and her family arrived, the Terezin facility was converted to a concentration camp/ghetto. Fifteen thousand children passed through Theresienstadt, and Edith was one of them. She and her mother were separated from her father. A few short months after arrival, he got a bladder infection, was taken to the “infirmary,” and died. Edith was in Theresienstadt for two years with her heroic mother who befriended the cook who at great risk gave her extra food. Flora shared it with the most needy in the barracks. Edith was there when the Red Cross came in June of 1944 to inspect the camp, and Edith witnessed first hand the charade the Nazi’s put on to convince the world that they were good to the Jews. Afterwards, they actually filmed the fakery as propaganda. Soon thereafter, Edith and her mother boarded a transport for Auschwitz.

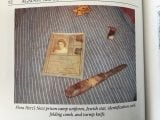

Edith recalls being one of the lucky ones; she and her mother survived the days of transport to Auschwitz—“too many other died in the cattle cars.” Everyone from the Theresienstadt transport was taken to Auschwitz II or Birkenau, established in 1941 as an extermination camp. Birkenau included a camp for new arrivals as well as a family camp, a gypsy camp and a women’s camp. Edith and her mother were sent to the family camp with everyone from the Terezin transport. Luckily, she was able to be with her mother. The next day, Edith got her tattoo A-2676. They were quarantined there with no work, just an endless routine of roll calls. Edith hoped for work detail, deportation to another camp; otherwise there would be the crematorium. One day Edith was chosen by her birth date for selection by Dr. Josef Mengele. She pleaded before him that she had a mother who was “strong. She can work.” He answered, “Bring her here.” Flora came before him and they both were sent to the right.

They entered Auschwitz with about 100 other women and sent to disrobe and “shower” in the “little Red Brick House.” By some miracle that day, the gas chambers didn’t work, and they lived. Although her mother considered one time throwing herself onto the wires, according to Edith, “for the most part we remained optimistic…My mother and I wanted to live, to survive the camps, and be reunited with my sister, Suse, and tell the story.”

In July 1944, Edith and her mother were selected once again for transport, this time to Stutthof in northern Poland. There Edith met up with her future husband, Henry Lucas and others from Duisburg. She was chosen for work detail and received a shirt, a coat, a blanket and good boots which would become lifesavers in the months to come. She was transported farther east to dig ditches in September of 1944. By winter of 1945, it was snowing and Edith and the others were malnourished and exhausted. She and her mother were very ill. Her feet were frozen and she couldn’t walk. On January 26, 1945, while sheltered in a farmhouse, they heard gunfire. The Nazis had left them with the advance of the Russian soldiers who “liberated” them. According to Edith, “we were liberated in the literal sense, but we still had quite a journey ahead of us before we could really feel a sense of freedom.” During this time they managed to write letters to Suse in Coventry to try to reunite with her. ( Refer to Suse Rosenstock’s Registry for letters).

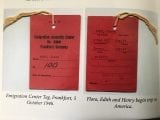

Liberation

By March 1945, Edith was feeling well enough to leave Nowe Miasto. Edith and her mother were now considered displaced persons. Warsaw and Berlin lay in rubble. They had no place to live and went to a Jewish refuge home in the French zone. By December 1945, after three and a half years, they made it back to Duisburg. It was the first time they felt liberated. Edith, her mother, Henry Lucas and few others were the only survivors from Duisburg out of 809 Jews. First Edith and her mother were hospitalized. Then, when they were released, British soldiers gave them an apartment in the British zone. Edith desperately wanted to go to America where her sister, Suse was living with their aunt Alice in Brooklyn. Edith desperately wanted to see her sister, Suse. Edith and her mother. They registered in Bad Wildungen (where their mother was born) part of the American Zone to assure immigration to America. As Edith describes it in her memoir, “Immigration was not a fast or easy process.” They passed their medical exams at the American embassy in Frankfurt, and then they waited. In February 1947, they were finally assigned to a ship. They arrived in New York harbor eleven days later. Edith’s mother gave a photograph of Suse to the ship’s steward who came back later and said he recognized her daughter, “I saw her in the luncheonette. I told her you are on board waiting to disembark.” Edith describes with joy the “sweet reunion” with Suse. At the time of reunion, Suse was sixteen years of age. Edith, her mother and Suse began their new life in Brooklyn at 907 Nostrand Ave. in a small apartment above a hat store living with her aunt Alice and uncle Felix and their children and a host of extended relations.

Post-War America

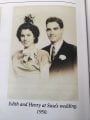

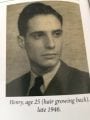

In the post war period in the United States, Edith and Henry Lucas had two children, Jerry Allan, born in 1954 named after Henry’s father Joseph and Edith’s father, Albert, and Ruth Sandra, born in 1956, named after Henry’s sister, Trude and Edith’s aunt Sidonie. They settled in New York City and Henry bought several dry cleaning stores. Life was good for Edith and Henry in the post-war decades raising a family. Tragically, Henry died in a ski lift accident on February 18, 1973. Edith’s son was in college, but she had the support of her sister Suze and her family. In 1974 she met a widower, Arthur Pagelson, and they married on June 15, 1975. Arthur passed in 2004.

Editor’s Note:

Edith passed on October 7, 2023 at the age of 97. -

SURVIVOR INTERVIEW:

Refer to Biography and the Edith Lucas Pagelson’s memoir, Against All Odds : A Miracle of Holocaust Survival.

-

Sources and Credits:

Credits:

Biography by Nancy Gorrell adapted from Against all Odds: A Miracle of Holocaust Survival by Edith Lucas Pagelson; Digital historic and family photographs and documents from Against All Odds.

SSBJCC Holocaust Memorial and Education Center gratefully acknowledges the donation of Against All Odds to the Holocaust Memorial and Education Center by Edith Lucas Pagelson. The memoir is available online and at Amazon.com