- Local Survivor registry

- Fran LETZTER MALKIN

- Local Survivor registry

- Fran LETZTER MALKIN

Survivor Profile

Fran

LETZTER

MALKIN

(1938-PRESENT)

PRE-WAR NAME:

FEYGE LETZTER

FEYGE LETZTER

PLACE OF BIRTH:

SOKAL, EASTERN GALICIA

SOKAL, EASTERN GALICIA

DATE OF BIRTH:

APRIL, 14 1938

APRIL, 14 1938

LOCATION(s) BEFORE THE WAR:

SOKAL, POLAND

SOKAL, POLAND

LOCATION(s) DURING THE WAR:

SOKAL, UKRAINE

SOKAL, UKRAINE

STATUS:

HIDDEN CHILD SURVIVOR

HIDDEN CHILD SURVIVOR

RELATED PERSON(S):

ELI LETZTER - Father (Deceased),

LEA MALTZ LETZTER - Mother (Deceased),

MOSHE MALTZ - Uncle (Deceased),

SHMELKE LETZTER BROTHER (Deceased),

HERBY MALTZ - Cousin,

JUDY MALTZ 2ND - Cousin,

RIVKA MALTZ - Grandmother (Deceased),

DEBRA SCHONBERGER PIERCE - Daughter

-

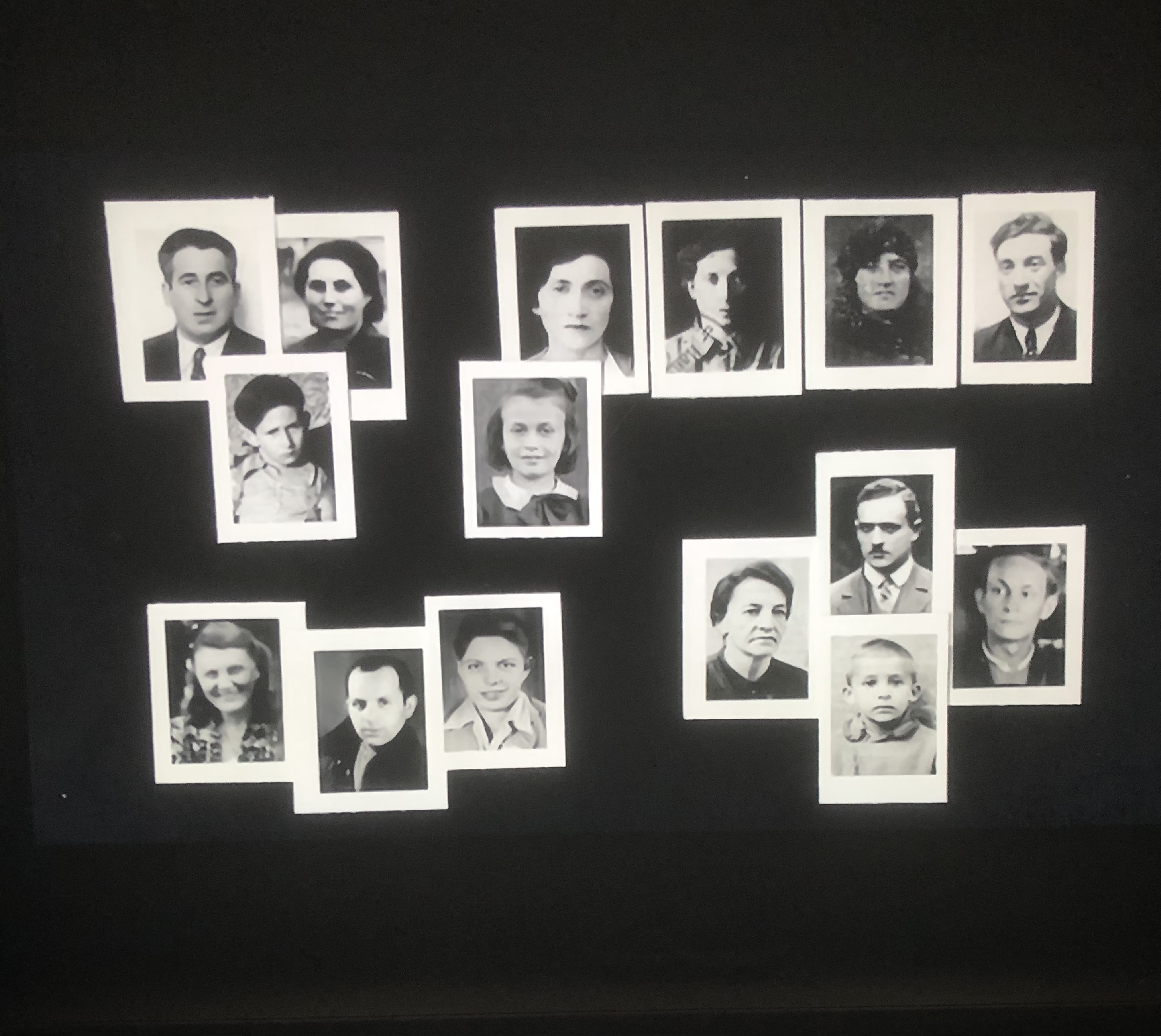

BIOGRAPHY BY Fran MALKIN "YOU MUST NOT CRY"

Fran Malkin does not consider herself a writer, but she attended a “Leaving-a-Legacy” Writing Workshop for Holocaust Survivors at Drew University. She wrote in the workshop a memory entitled, “You Must Not Cry” for the collection, Moments in Time subsequently published by Drew University, Madison, NJ in 2005. Fran, sometimes referred to as Frances or Fay as her family prefers to call her, relates the story of her survival below.

SURVIVAL STORY OF FRAN MALKIN, “YOU MUST NOT CRY”

“You must not cry,” everybody was insisting. “She must not cry-we will all get caught and be killed.” We were in the attic of the barn. The pigs were downstairs and Mrs. Halamajova started beating the pigs so their cries would overshadow my cries. I had been told over and over in the ghetto that I must not cry in the attic. I promised I wouldn’t cry. One uncle said, “Don’t bring her-she is only three maybe fours years old. Maybe you can leave her at a church, and the priest would take her in and raise her.” But my other uncle and my mother said, ‘We are not leaving her; she is coming with us wherever we go.”The place to go was a farm outside Kokal, Poland, owned by Mrs. Halamajova and her daughter Hela. We called her the Angel. She made a commitment to my family that she would hide us in the attic of her barn. We arrived late one night as the Sokal Ghetto was being liquidated. We climbed under the barbed wire and stealthily made our way to the barn. Our little party consisted of my uncle Shmuelke, my mother, the prominent Doctor Kindler of our town, his wife and two sons. My uncle befriended him and offered him what he felt was a safe hiding place where the Nazis would not find us.When we reached the barn, we found the pigs, whose home this was, downstairs. There was a ladder that led up to an opening in the attic. We climbed it and the door was raised up, and we entered the attic. Then the trap-door was lowered. There were six more members of my family there. My father was not among them. He was taken away when the Germans entered Sokal, supposedly for labor-but was never heard from or seen again.The attic had straw on the floor. The adults could not stand up straight. There were down feather beds on the floor where my uncle, aunts and grandmother had already been staying. There were German soldiers in the surrounding area. The turmoil of gunshots and soldiers and people screaming was all around. And all I could do was cry. And the more everybody begged me to stop, the less I could control myself. The pigs were crying, and I was crying.The decision was made. The lives of thirteen people and Mrs. Halamajova would not be threatened by the cries of a four-year-old child. Dr. Kindler had brought medications with him and poison was included, in case we needed it if we were caught. Two men held me down in the straw and a little pill started being shoved into my mouth. Big fingers were pushing the pill in, and my little fingers kept shoving the pill out. I kept pleading, “I’ll be good, take the pill away.” But the fingers kept pushing the pill in-and my little fingers kept pushing it out.And then there was silence.“May God forgive you-I forgive you” were my mother’s words. They waited for everything to be still, and then Mrs. Halamajova came with a sack to put the body into and to take down to the river. The doctor came over and picked up my hand and felt a pulse. Through my burned and bruised lips I whispered, “Mama, Ich Leb!” (“Mama, I’m alive!”)A MOMENT FROZEN IN TIMEMemories-so many fragments-how do I start? I was born in 1938-so my first memories are in the ghetto of Sokal, Poland. I was two, three, or maybe four years old-I don’t have a time reference.An incident-I had typhus-we lived in a room-I was in a bed, sick-my mother was in another bed-my grandfather Shmuel was in another bed maybe in another room. He was my father’s father. My father was taken away when the Germans entered Sokal, and he was never seen by my family again. I never knew him.Everybody in that room had typhus and the big fear to me was nighttime-because when night-time fell, the fevers rose so high that everybody became delirious. My mother and my uncle Shmuelke, her brother, would jump up out of bed, they would scream, they would jump around, they would be manic and frightening. At one point Shmuelke put his hands around my mother’s neck and said “I love you so much’ and started choking her. I have difficulty describing the horror of the visions before my eyes.I lay quietly on my cot. I was not going to behave that way. It was all going to be internalized.It is a moment frozen in time.Other moments-the Germans were doing another Aktzie (a roundup of Jews in the ghetto)-there were three Aktzies in our ghetto.My mother’s father, Yosef, was bedridden and he was left in the room because we were all going into hiding in a pantry or basement in that house….Mrs. Halamajova, the AngelIt is very difficult for me, in this group, to recount incidents, in detail, of my war experiences. I was three-four-five years old. I remember fragments or pictures that have stayed embedded in my mind-I can’t tell a full story. I was an observer. No opinions were asked.We were hiding in the attic of a barn in Sokal, Poland, the pigs downstairs and thirteen of us in the attic. The straw was our floor and bed-and down bedspreads our coverings. The unique Polish woman who cared for us risked her life and her family’s by standing up to the local Germans and Ukrainians. They constantly tried to run her out of her home and take over her property. They posted threatening notices on her door. But her continued position was that she could not give up her property because we would be discovered. We called her the Angel. She hid us for two years.As the war with Russia progressed eastward, she was forced to have German soldiers quartered in her house. And then the battle was brought into Sokal. The Russian soldiers came. The bombs were going off all around us, the warplanes were flying overhead, and there was shooting all around. We huddled under the down comforters in the old barn.The decision was that it was too dangerous to stay in the barn. The Russians had overrun the town and it was best to go back to our family home. The Russians were not our enemy. At that point, Mrs. Halamojova, the Angel, came to us and informed us she had hidden another Jewish family in her basement throughout the war. She also informed us of another problem. One of the German soldiers quartered in her house realized the war was lost and asked her to hide him. She hid him in another attic in her house. Her request, now that the Russians were here: would we take him with us and say he was Jewish?What memory serves me is a lot of arguing and shouting among the adults in the attic. For two years of our lives we only spoke in whispers. Now there was an explosive situation. “How can we take him and say he is a Jew? How can we try to save a German soldier? They are murderers. Why take one of our murderers and try to save his life by passing him off as Jewish?” was one of the arguments. And the other argument was, “But if the Russians find him and Mrs. Halamojova, they will arrest and execute both of them, him as a German soldier and her as the person who harbored the enemy.”We did not take him. That night the Russians made a raid on her house and found them. They were both arrested, the German soldier and Mrs. Halamojova. My family went and pleaded with the Russians to release her-she saved all these Jews in her attic and basement. Their position was that she deserved a medal for saving Jews but should be hanged or imprisoned for harboring the enemy. Finally we prevailed and she was released. They let her go home. But my uncle didn’t trust them. He went to her house first and found Russian soldiers waiting for her. That night, he walked her across the border to the family of hers in another town in Poland. She never saw her home again.I occasionally think about the incident and the morality of everyone involved.CHAYE DVORAChaye Dvora was in her twenties. She had dark curly hair and dark smiling eyes. That’s how I picture her. But what I remember most is her terrible coughing. She was surrounded by her mother, sisters, and brothers, who had to watch her choke on her coughs for fear that the noise would alert a neighbor to people hiding in the barn. In the attic swarming with lice, her cough was made worse by the dust swirling up from the straw on which she lay. For months, her mother watched helplessly as her daughter slipped away. Even the doctor hiding with us could not control her fever or do anything to relieve the spasms from tuberculosis. Instead of fresh mountain air, good nutrition, and meaningful medical attention, she had to slowly suffocate in the airless attic above the pigsty. How ironic that pigs below us could grunt and snort, living as they pleased. Jews were not accorded the same privilege.One night she died. A sheet was put up between where she lay and us children who moved the sheet slightly to see her body being wrapped by her brothers in a blanket. In the darkness of the still night, they stealthily carried her down from the attic and buried her beneath a tree.Since she was not allowed to have a life that flourished, some acknowledgment of her being has to be remembered-she was my aunt, my mother’s sister.DP CAMPDon’t let her touch the baby. She just touched his hand, oy, oy, oy-get her away from the baby!” I was about eight-nine years old and this was my aunt Chana yelling hysterically.We were in Austria and it was after the war-the DP camps. After we fled Poland and all the agony and losses imposed on us by the Nazis, we finally reached a destination where there were Americans and we were given places to live and we were free.We were also given medical exams. I was given a Roentgen or chest X-ray. I was called back with my mother-I had tuberculosis. This is very contagious. The authorities who ran the camps sent me to several sanatoriums. Some with my mother, some on my own-and from time to time I returned to the DP camp.My aunt had just given birth to a beautiful baby boy. Everybody made such a fuss over him and I wanted to touch him too. Her reaction, and other people’s reactions, imprinted such a hurt on me-I think it molded my personality and reactions to life in a greater sense than the war. In the war we were all equal. Now I was being punished and forced to retreat into myself. I wasn’t allowed to breathe on or touch anyone. I suppose they were right, but I don’t think that I ever truly forgave them for what they did to me.The TB and its effect on my early life have molded my entire life and what I became to this day and how I have responded to the world around me.THE LETZTER FAMILYI wake at night and across from me there is the picture-my father and the other men in the group-a Zionist organization in Sokal. All handsome, stylishly dressed, intense young men in their twenties and thirties. How striking, intense, and hopeful they all look. My father talks to me-he communicates with me. He last spoke to me when I was two years old and he was taken away for “work” detail. We never saw him again. The local people told us they were all taken to dig their own graves, and shot. What hopes and dreams he had for his life!I, his only child and the last survivor of the Letzter family, spent my life avoiding and tuning out any thoughts of that family, because to do so would have consumed me. But now the picture talks to me-haunts me. The burden I carry of being the last one and how I was to carry on the legacy. I now realize that to have dwelt on this would have immobilized me. The wounds were there but they were invisible and were sublimated by the life choices I made.Now attention must be paid to the consequences of my actions. Faith-I can only ask: “Why did this have to happen?”The injustice and the rage I feel by opening these wounds.I have tried not to go there, but now I must, and I am scared.A PHOTOGRAPHThe year was 1940, maybe 1941, my mother cannot respond to that question today.The Nazis entered Sokol and had all able-bodied men gather at the center of town. The old and sick were sent home and the young and vigorous were assembled and marched off to “work.” The order had gone out that morning and my father held his 2 year old little girl in his arms and wept, and then he relinquished me to my mother’s arms and departed.After the war we were told by the Ukrainians they were led out to a field, dug their own graves and were shot. Life, as seen in the attached photo, ended for my mother that day also.She has lived a long life. It has been a shell of an existence. It was always her and me and not a day went by without my mother mentioning his name, Eli. I accepted my life as a person with a mother only and buried my conscious thoughts of a father-for me that concept was unreal and unknown. That years of therapy only concentrated on my search for a father figure, I never fully comprehended. Except in my choices and needs of people.My mother never recovered or participated in any joy of life. And everything she became and felt was passed on to me and on to my daughter. Life is a cycle. Maybe she has more peace and comfort in her present state. However, I think deep inside her it’s all still there.I wish I had known the people in that photo. -

INTERVIEW with fran malkin, child survivor

Date: May 5, 2021

Location: Malkin Residence, phone interview

Interviewer: Nancy Gorrell

Q: Describe your family background.

A: My family came from Sokal, Poland. It was our family home for generations. My mother’s father was in the cattle business. They were well-to-do people. The Letzters, my father’s family owned a lumber yard.

Q: What kind of place was Sokal?

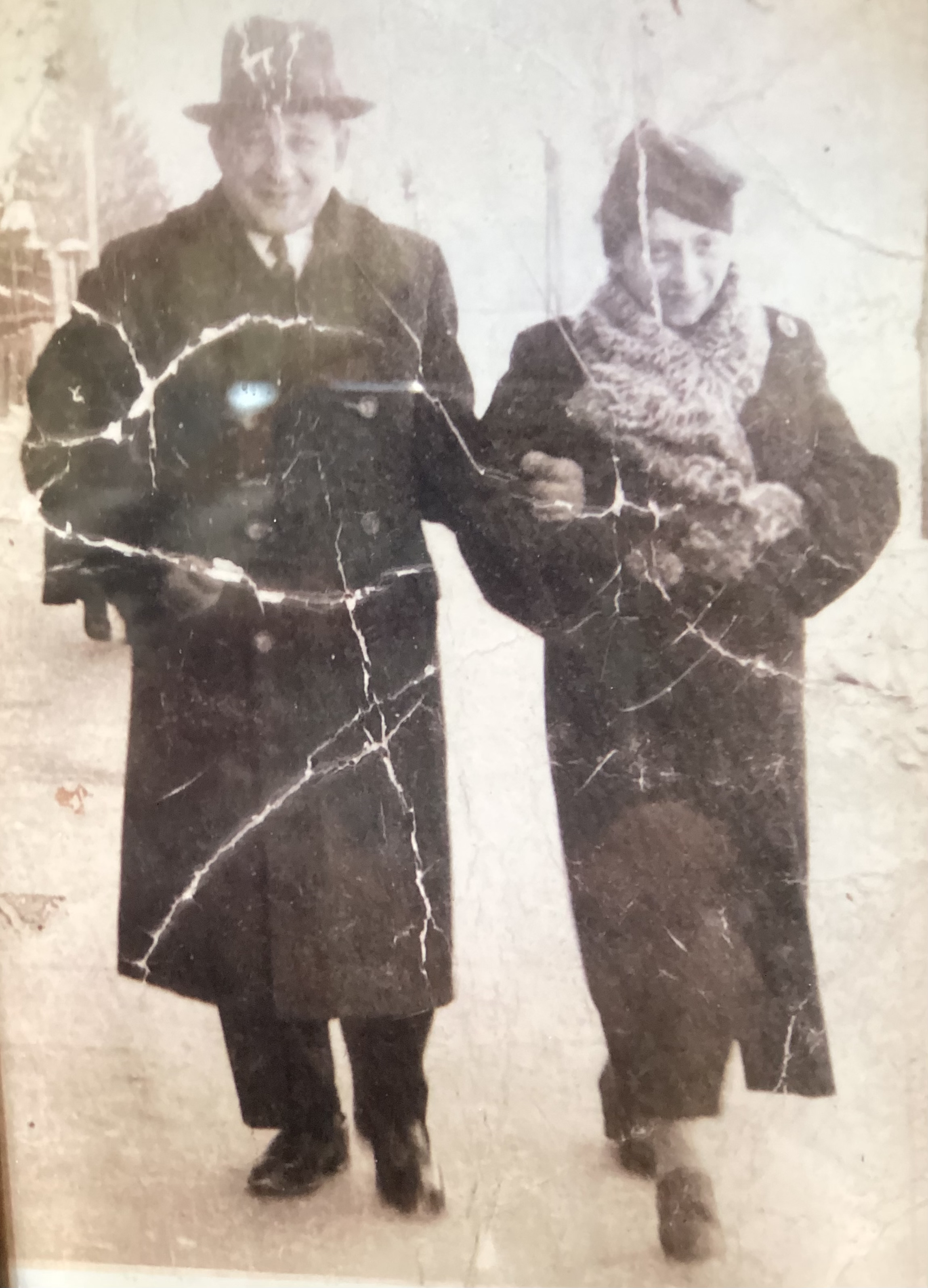

A: It was a small, cultured city. Whenever I begin my talks to students, I show them this photograph of my parents (Fran shows photograph to interviewer). She asks “What do you think of the way they are dressed?” (Refer to photograph of Fran’s parents in Related Media of parents dressed in distinguished, long fur coats with warm hats).

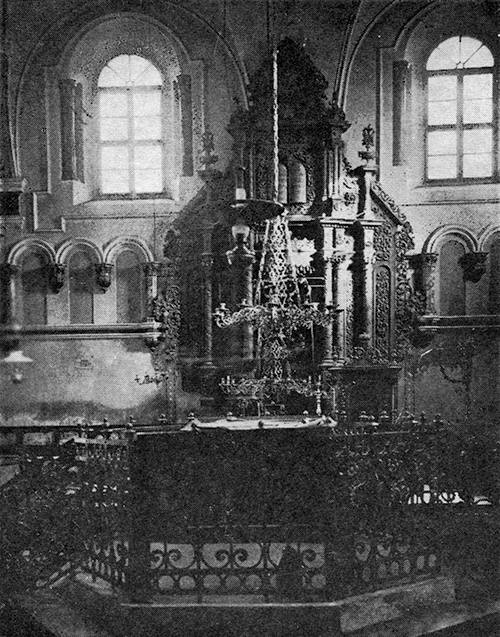

Q: Sokal had a synagogue at the time of the war and 5400 Jews (Refer to Historical Notes below). Was your family observant? Did they go to synagogue?

A: Yes. They were observant but modern, not Hasidic.

Q: What did your parents do for a living?

A: My parents owned a candy store in Sokal (Refer to photograph of storefront in Related Media). They were educated, well off, middle class people.

Q: Describe your parent’s families.

A: My mother had two brothers and two sisters and my father had three brothers and two sisters. They all perished on my father’s side. I don’t know where they were all killed. Some were gassed in Belzec.

Q: Do you know how or where they perished?

A: On my father’s side, the majority perished in Belzec. My mother’s side went into hiding with us and my grandmother Rivka.

Q: In Francisca Halamajowa’s hayloft above her pigsty?

A: Yes. Thirteen of us were hidden in the hayloft for 22 months. My mother’s sister Chaya Devora died from TB while we were hiding. When we were leaving Sokal, Rivka was later killed in an accident after the war.

Q: What are your earliest memories?

A: My earliest memories are from the ghetto. I guess I was three and half or four. The Sokal ghetto was a couple of blocks enclosed by barbed wire. My whole family—my father’s side and my mother’s side lived in one room with other people too. I remember disease, typhoid and sick people. People were dying. There were no medications. You either died or lived.

Q: What else do you recall?

A: Someone in the ghetto had set up a place to bake in one of the rooms. My aunt took me there and I ate a delicious napoleon. Afterward, I told my grandmother, my father’s mother, that I was going to take her there the next day. That night she was taken in the second aktion. My daughter Debra is named after her.

Q: What else do you know that happened to your family in the ghetto?

A: The railroad trains passed right through the ghetto and went directly to Belzec, a death camp an hour away. What they did was they got all the Jews in one place. They would have aktions and they would round up all the Jews of the ghetto and then they would send them directly to a gas chamber and the bodies would be burned and then the train would come back to Sokal. And then they had Jewish workers like my uncle that had to clean out the trains coming back from Belzec.

Q: How many aktions do you know that occurred in Sokal?

A: There were three aktions.Q: When did you first realize what happened to your father? Or rather that your father went “missing.”

A: In June 1941 the Germans rounded up 400 Jewish males in the Ghetto for “labor.” After the war we found out that the Jewish men were taken to an old brick factory outside of Sokal, made to dig their own graves and shot. We only found out about it after the war when we were liberated July 1944.

Q: How did your family manage to go into hiding?

A: My uncles used to sneak out of the ghetto at night and they would ask their Polish friends to hide them. Everyone said no, but Francisca said, “yes.” When the third aktion happened—liquidating the ghetto, we sneaked out at night and walked to her house. I remember specifically walking to her house at night.

Q: What is your memory of the house?

A: She had a barn behind her house and she kept her pigs downstairs. There was a ladder that led up to a trap door. We walked up the ladder and entered the hayloft. There was straw on the floor. We slept on the straw. The adults could not stand up straight. There were 13 of us including Dr. Kindler, his wife and his two children. I was with my mother and her family. We spoke in whispers.

Q: May 28, 1943—”The Day You Almost Died” is well-documented in your uncle’s Moshe Maltz’ diary and John Ward’ article for Drew Magazine. You first wrote about the incident in the hayloft in a survivor writing workshop at Drew University. What do you recall about that day?

A: What I remember most about that day was crying. (Fran takes out Moments and reads a passage to the interviewer entitled “You Must Not Cry”). The decision was made…Dr. Kindler had brought medications with him and poison was included in case we were caught. Two men held me down in the straw and a little pill started being shoved in my mouth. Big fingers were pushing the pill in and my little fingers kept shoving the pill out. I kept pleading, I’ll be good, take the pill away. But the fingers kept pushing it in and my little fingers kept pushing it out. And then there was silence. (Refer to Extended Biography above for the entire memory from Moments).

Q: Yet you lived to tell. Do you struggle with forgiveness?

A: I never held the incident against them or Dr. Kindler. They had to survive. They did what they had to do.

Q: What about your mother? In his article, John Ward mentions you “didn’t get along well.”

A: Yes, but that was more from over-protectiveness, not from the incident.

Q: How long were you in hiding in the hayloft?

A: For 22 months, almost two years. We were liberated by the Soviets on July 19, 1944. While we were in hiding, my mother’s sister died of tuberculosis.

Q: Describe your liberation experience?

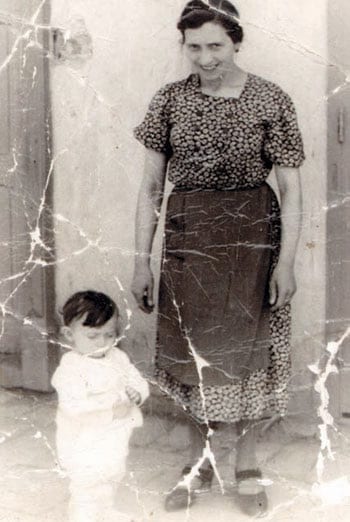

A: When I was in the Displaced Persons Camp, they found out I had tuberculosis and I ended up in a sanitorium in the American DP Camp Ranzhofen and Ebelsberg, Austria. I spent three years in DP camps much in isolation from family and others. The photograph of me used for “The Day She Almost Died,” I was eight years old and in the DP Camp (Refer to photograph of Fran in Related Media).Q: How did you family emigrate to America?

A: My mother had an uncle and he sponsored us and we came to Boston on January 17, 1949. The whole family came, what was left of us, the Letzers, me and my mother and the Maltz’s.

Q: When did you begin speaking about your Holocaust experiences?

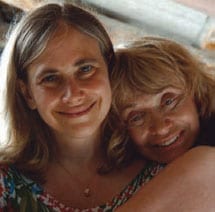

A: I only began in the last ten years. It was as a result of the making of the film, No 4 Street of Our Lady by my niece, Judy Maltz in 2007. The filming brought me with my cousin Herby Maltz back to the scene—Sokal, the brick factory and the railroad tracks and the hayloft. After that I began to speak to students in schools. Today I get calls to speak almost every week. I may have spoken at least 25 times to hundreds of students this year on Zoom.

Editor’s Notes:

The film No 4 Street of Our Lady was released in 2009 and co-produced by Barbara Bird and Richie Sherman. Available online at amazon.com

Refer to Historical Notes below for Jews of Sokal history.

-

HISTORICAL NOTES:

Destruction of Sokal by Daniel Abraham

(Refer to danielabraham.net) for complete History of the Jews of Sokal )

Fay Letzter Malkin who was born in Sokal and survived by hiding in a barn for 18 months wrote (via the Jews who come from Sokal FB group):

“My father, Eli Letzter, was killed when the Germans came into Sokal and ordered all Jewish males to report for work and they selected 400 and took them out to an old brick factory and shot them.”

“Sokal is mentioned by Father Patrick Desbois in his book “The Holocaust By Bullets”. He interviewed people there. Father Desbois told me that Sokal was the first place the Germans carried this out. “

Yahad-In Unum is an organization dedicated to locating the sites of mass graves of Jewish victims of the Nazi mobile-killing units in the former Soviet Union founded by Patrick Desbois. Here are their findings regarding mass executions of Jews in Sokal: (via Fran Fay Letzter Malkin / Jews who come from Sokal FB group)

“According to the Soviet extraordinary commission conducted just after the liberation and the German archives, there were four executions in June 1941. The first one was conducted on June 22, 1941, the same day the village was occupied, against 11 Jews who were shot dead in front of Polish cathedral. Then, there were three more in the course of three days, from June 28 to June 30, when 17 Jews, 117 Jews and 183 Jews were shot respectively. Prior to the execution all those Jews were confined in the brick factory and then murdered not far from it. [The information about what happened to them before the shooting is different from Moshe Maltz’s memoir.] Unfortunately, we didn’t find any eyewitnesses to this shooting or to what happened before. But this execution site normally had a memorial at the time of our investigations and it is located by the road leading to Tartakiv.”

“There were several deportation waves, one deportation as conducted on September 17, 1942, when 2,000 Jews were deported to Belzec and about 160 shot dead of the spot. Another one was conducted after the ghetto was established in Sokal in late October when about 4,000 Jews were deported. The ghetto was liquidated on May 27, 1943. During the liquidation some 3,000 Jews were shot, according to the Soviet archives but this number might be overestimated. According to the local witness, the shooting was conducted in field located between Sokal and Ravshchina. The shooting was conducted during the day and the road was blocked in order to prevent the collateral victims, so some people were stopped on the road and could hear what was happening until the execution was over.”

Today

Today, there are fewer than 10 Jews out of a total population of over 25,000 people. What was once the center of the Jewish community of Sokal is now a park, the ancient fortress synagogue is in ruins, while the former Jewish cemetery is a residential zone with no signs or markers (source: jewishheritage.org.ua (pdf)).

-

Sources and Credits:

Credits:

SSBJCC Interview with Fran Malkin, May 5, 2021; Biography of Fran Malkin, “You Must Not Cry” qtd in Fran Malkin, Moments in Time 2005 (54-58) Drew University, Madison, NJ.

The Center gratefully acknowledges donation by Fran Malkin of No. 4 Street of Our Lady (video copy) as well as reproduction of historic photographs therein and Fran Malkin, “You Must Not Cry,” Moments in Time (54-58) Drew University, Madison, NJ. No 4 Street of Our Lady available on Amazon.