- Local Survivor registry

- JACOB WEINGLASS

- Local Survivor registry

- JACOB WEINGLASS

Survivor Profile

JACOB

WEINGLASS

(1920 - 2023)

PRE-WAR NAME:

JACOB WEINGLASS--OLDEST CENTENARIAN (AGE 103)

JACOB WEINGLASS--OLDEST CENTENARIAN (AGE 103)

PLACE OF BIRTH:

ODRZYWOL, POLAND

ODRZYWOL, POLAND

DATE OF BIRTH:

NOVEMBER 25, 1920

NOVEMBER 25, 1920

LOCATION(s) BEFORE THE WAR:

ODRZYWOL, POLAND; LODZ, POLAND

ODRZYWOL, POLAND; LODZ, POLAND

LOCATION(s) DURING THE WAR:

LODZ, BALUTY GHETTO, BIALYSTOK, KAZAKHSTAN, BALKHASH, SIBERIA, UKRAINE.

LODZ, BALUTY GHETTO, BIALYSTOK, KAZAKHSTAN, BALKHASH, SIBERIA, UKRAINE.

STATUS:

SURVIVOR, REFUGEE

SURVIVOR, REFUGEE

RELATED PERSON(S):

SARA DEREN WEINGLASS - Spouse (Deceased),

LEON WEINGLASS - Son,

MARK WEINGLASS - Son,

3 GRANDCHILDREN ,

8 GREAT GRANDCHILDREN

-

BIOGRAPHY BY NANCY GORRELL

JACOB REQUESTED THE FOLLOWING ANECDOTE BE ADDED TO HIS REGISTRY:

In the spring of 2018, I saw Jacob during one of his visits to the Center. At that time, I told him he was our oldest living survivor and congratulated him for living. He smiled and then asked, “Do you know why?” I shook my head. “Because G-d won’t let me die. He doesn’t want to answer my question. You know the question?” “No, I answered. And he looked at me and said with a smile, “Lamah Azavtanu—why did you abandon us?” Jacob plans on living a long time. And he did.

Postscript: Jacob Weinglass passed on May 7, 2023 at the age of 102.

BRIEF BIOGRAPHY

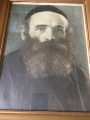

Jacob Weinglass was born in Odrzywol, Poland, a small village of only 100 people. He had six brothers and four sisters. His father, Mendel, moved the family to the industrial city of Lodz in 1928 to open a shop with a relative who lived there. Jacob began working in the shop when he was 13 years old “at a meager salary” to help support the large family. He was the only working boy in his family. The others were in the yeshivas and the younger ones were too weak to work. Mendel’s father was a deeply religious man who went to synagogue every week.

When the German army invaded Poland in September 1939, Jacob was an 18 year-old boy on the brink of manhood. As he tells it, “I saw what was going on.” At that time the Jews had to wear the yellow band. Jacob refused to wear the band. He was “street wise,” smoked and knew how to “mix” in with the peasants. He talked to his father, “Let’s get out of here.” He knew Jews were fleeing to Russia. His father refused to go to Russia because it was not “kosher.” He didn’t believe the Germans were as bad as the Poles. In a few months (January, 1940), the Baluty ghetto was formed. A Polish boy pointed Jacob out to the police for not wearing the armband. He hit the boy. After that, Jacob didn’t go home anymore. He went to a relative. He tried to persuade the relative to go to Russia with him. The relative refused.

As Jacob tells it in his interview, “All young people from 18 had to go to Warsaw.” Jacob and his brother decide to flee. They hid out in the fields together, but they are captured by the Germans and accused of being traitors. Jacob’s brother says they are watchmakers. He fixes a Nazi officer’s watch. They are released.

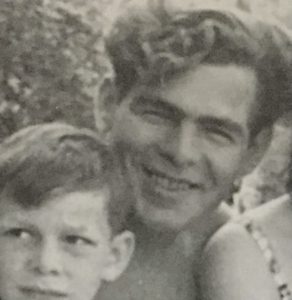

Jacob’s story is one of a refugee boy, caught in the chaos of war-ravaged eastern Europe with hundreds of other refugees, as the German and Russian armies clashed in numerous battlegrounds and border areas. Along the way, Jacob is captured by both the Germans and Russians, talks his way out of capture with the Germans, is jailed by the Russians in Pinsk and is ultimately released from jail there by the Jewish community. In his interview, he describes his experiences fleeing—“thousands of people like cockroaches,” the starvation, “eating snow,” making his way to Bialystok and Pinsk and then finally, going to Kazakhstan as the Russians round up able-bodied Jewish boys for labor. On the way he is with his future wife, Sara Deren, another refugee, who is with him for the duration of the war. They marry in Russia and have a son, Leon, while in Kazakhstan. Jacob works at hard labor in Kazakhstan where he learns the ins and outs of piping and plumbing. Life is harsh and elemental. After three years there he “wants out” no matter what and agrees to go to work in Siberia despite the warnings that it is worse. Jacob spends the remainder of the war working in Siberia where he dismantles factories and armaments.

Three of Jacob’s brothers survived in Poland. One brother survived in France. Two sisters died in Auschwitz. One sister died as a partisan in the woods. His father died from starvation in Lodz ghetto. His oldest brother went to America in 1905 and was working as a chaplain in the U.S. Army at the time.

After the war, Jacob went to lower Silesia to work in a factory for the Russians. When they transferred the factory to Wroclaw, Poland (refer to notes: Battle of Breslau), he moved his family there. In Wrocław a second son, Chaim was born. They lived in Wrocław until 1957 when the Polish borders were opened to emigration to Israel. Jacob and his family lived in Israel until 1961 when Jacob decided to move his family to America to be with his brothers who had settled after the war in the Newark, New Jersey area. Jacob made his living was as plumber, an experience he learned in Kazakhstan. Jacob and his family eventually settled in Maplewood, N.J. where they lived until he retired in 1986.

Editor’s Notes:

Jacob remains the Oldest Survivor in our Center’s Registry to date.

Refer to Historical Notes Below for Bialystok and the Battle of Breslau.

-

SURVIVOR INTERVIEW:

JACOB WEINGLASS INTERVIEW

Date: December 2, 2016 and May 15, 2017

Location: Weinglass Residence, Somerset, New Jersey

Interviewer: Nancy Gorrell

Q: When and where were you born?

I was born on Nov 25, 1920 in Poland in a town called Odrzywol— a very little town of only a hundred people at the time, a town in east-central Poland. My father Mendel Weinglass called me many names. Why so many names? Whenever I was sick my father gave me so many names to cheat the angel of death. I had six brothers and four sisters, but they are all gone. I am the only survivor.Q: What was your early childhood like?

I grew up Lodz. We moved there in 1928. My mother took care of all the children. The Germans, when they occupied the town, named it Litzmannstadt. It was the second largest city in Poland, an industrial city, producing textiles. I had a relative in Lodz that owned a factory but went bankrupt but then he opened a smaller shop in my father’s name, and I worked in the shop to do my father a favor. I started working when I was 13 years old. I was in school until third grade. During “intermission,” the kids would play. The kids called for me to kick the ball. They told my father I was playing soccer. My father said, “You’re going to grow up a gentile?” He pulled me out of school. So I went to the rabbi for education in a cheder. I didn’t want to go to the cheder. I grew up without much of education. Everybody was supposed to attend school.Q: Was your family religious?

My father was a very religious man. He took me to synagogue usually Saturday every week. Right from the services, I went to the factory because Saturday was the payday. My father didn’t know that. Now I only go to the synagogue for the holidays and yizkor.Q: What was work like for you?

I was the only working boy in the family. The others were in the yeshiva and the younger ones were too young to work. I got a meager salary every week.Q: Did you experience anti-Semitism in those years?

Anti-Semitism? Poland was a good place for anti-Semitism. My father hated the Poles more than the Germans. My father was a soldier in the old Russian army—czar Nicholas’ and he got a bronze medal. My oldest brother went to America 1905 and became an army chaplain. When my father saw a picture of that, he cut off his beard and sat shiva. He said he lost a son. In the 70s my oldest brother went to Miami, and he opened a synagogue. The synagogue is still in his name there: Rabbi Yitzak David Vine.Q: What happened to you and your family when the Nazis invaded?

In 1939, I was 18 years old in Lodz when the Nazis invaded. All young people from 18 up had to go Warsaw. My older brother and me went 50 kilometers. We were hiding in the fields and then we saw red and white tanks. We started crawling near the road and all of a sudden the Germans were pointing guns at us, and they took us to the road and put us in a tank. We were questioned by high-ranking officers. They asked us about being traitors. My brother said we were watchmakers. My brother was given a watch. He fixed it for the Nazis. The Nazis told us to go back. We walked a half a day. All of a sudden the road was closed. We went to the left. We didn’t see anything. We went into the woods. We saw farmers and potatoes and fields for at least a mile. There were so many people there. We sat with so many people for several days. Finally, the Germans came and said we were free to go. So I jumped into a German horse and carriage. A guy started to protest. I kept going. I came to the first town. A day before some Polish soldiers machine-gunned German soldiers. My brother protested when I tried to jump in a car with some Germans, and he was taken as a prisoner of war for three months. Then he came back in January 1940 to Lodz. Right away he got a job as a watchmaker.Q: How did you and your family survive?

I was still a street boy. I saw what was going on. The Germans were going on the trucks picking Jews for work. At that time Jews had to wear the yellow band. I wouldn’t wear the band. I smoked what the peasants were smoking, and I mixed with them. Once I came home. I had to pass the main station. I came back. I saw ten people hanging in that square. “That Jew is a criminal,” they said in Polish. I talked to my father. “Let’s get out of here.” People were escaping to Russia. My father didn’t want to go. He didn’t believe Germans could do harm. Russia wasn’t kosher. He thought Germans were “higher class people” than Poles. I was fighting my father to go.Q: Did you go home again to Lodz?

One day I came home. Lodz was 40% Jews, 40% Germans, 20% Poles. Poles were the laborers. I encountered the volksdeutch, the police. A Polish boy pointed me out not wearing the armband. I struck the boy and he fell down. All the rich Jews were taken out of their apartments and sent to live in Baluty where I was living, the Ghetto. This was the beginning in January 1940. When I hit that boy, I didn’t go home anymore. I was afraid real bullies would be coming, so I went to a relative. I tried to persuade him to go to Russia. He refused. So finally I went by myself to Russia.Q: What was it like fleeing to Russia all alone?

I came to the border town, Malkin. Germans caught all of us and took us to a room and stripped us to find money. I heard the screaming and beating. When they found something, they beat the prisoners. Not all beatings were done by the Germans. Some of the beatings were done by the Poles. I was lucky. They let me go, except, I received a blow on the side of my head on my ear (Jacob points to his ear where he is hard of hearing). And two people grabbed me. I remember. There were thousands of people like cockroaches. When I woke up, I was covered with snow. I was so hungry. I started eating the snow. I was the only one left in the pass. I was sitting there. I remember this is the German side; this is the Russian side. They were yelling, “Give me back!” What should I give them back? But they started yelling at me. So they pushed me back in the natural pass half mile long. Late in the afternoon, the train arrives and the pass fills up. They saw me, and they asked me, “How many soldiers pulled you back? So they started organizing three groups to go in three directions—I was going into the Russian side. And that’s how I went to the next town, Bialystok.Q: What was Bialystok like?

Bialystok was so overcrowded with refugees. They took over the churches and synagogues. I was alone. I could stay for only 24 hours. The refuges got IDs with a date. You needed this to travel back and forth between cities. After a couple of months, I tried to go back to Poland. We paid a guide to show us the border. He took us right to the headquarters of the Russians who locked us up. Pinsk and the Jewish community bailed us out. Again we had to switch cities from Bialystok. Finally the Russians asked, “Who wants to go to work?” I went to register. I was sent to Kazakhstan. I asked, “What is Kazakhstan?” They said, “A big lake with fish.” We got contracts to go to work.Q: What was your time in Kazakhstan like?

There was nothing there, just a lake. No people, no nothing. At 5:00 pm, people came dressed in sheepskin clothes. They had army beds and giant tanks. They brought us pipes so we could make a pump and a shower from lake water. So ten people can take a shower at once. The people greet us with “sholem aleichem.” We find out later that they are living in the mountains in caves and holes. They had tables in the caves with Persian rugs and the floors with sheepskins. They were Muslims. I was in Kazakhstan three years living with the Muslims. It was ok, but not ok. At first we were 180 people. After three years only 40 left. After the three years, I got sick too. I spent time three weeks in the hospital (in a local town, Balkhash). I wanted out of there. I realized the country needs copper for the bullets. I said, “You need a watchmaker?” The Russians said, “You can go, but you will not like it.” “Where is it?” “Siberia,” they said. I said, “I will go, just let me out of here.”Q: What was your time in Siberia like?

I went to Siberia for two years. Later, the Russians trained me to dismantle factories. So I could dismantle factories in any town the Russians took. At the last minute, they said, “Jake, you aren’t going to Germany; you got to cross Poland, so what do I do?” They sent me to Ukraine. Me, in the Ukraine, receiving machinery? Only in the Ukraine did I get paid for my work. I was teaching thirty others how to work. In Siberia they cheated me.Q: What happened to the rest of your family? Did they survive?

My three brothers survived in Poland. One brother survived in France. Two sisters died in Auschwitz. One sister died as a partisan in the woods. My father died from starvation in Lodz ghetto. My oldest brother was in America working as a chaplain in the U.S. Army.Q: What happened to you after the war?

First the Russians sent me to a town Bialava. There was a factory in lower Silesia. I worked there in that little town. Then they transferred the factory to Breslau. I lived in Breslau, Germany until 1957.Q: Did you get married and have a family?

I got married in Russia. My wife and I went to Kazakhstan with the same group of refugees (about180 people, some Polish, some Czech, some Roma Jews). It was 1942. She was with me all the time. I lived with her 65 years. Her name was Sara Deren. In Russia and Siberia I got one son, Leon, and the other son, in Breslau. Chaim was his name in Breslau, but in the U.S., it is Mark.Q: Where did you emigrate from after 1957?

Our new Polish president opened the Polish borders in 1957 only to Israel. So we went to Israel. In 1957 the communists started cracking down. That’s why we left.Q: What was life like under the communists?

Terrible.Q: What was life like in Israel?

Israel was hard. We were there four years. My youngest son started going to high school. I had to pay tuition. My salary was 200 pounds. I worked in a factory. I received German machinery there. The Germans supplied the machinery—chemical pipe installations so this was a great hardship. I was working two jobs. I was living outside of Tel Aviv. I liked Israel; I didn’t want to go to any other place, but after two years, my other son had to go to high school. I had to pay for him too. The school was $80 for each son and I couldn’t do it. By 1961, all my brothers were in United States, and I wrote to my brothers to get me papers to get to the States.Q: When did you emigrate from Israel to the United States?

I came in 1961 with the whole family. My brothers lived in Newark, Hillside and Union. When the riots broke out, I was sitting in my house, and I was sitting watching TV. “Mister, your house was on fire.” I opened the door. Someone threw a molotov cocktail into the front of house. I was living on the border of Newark and Hillside. So when I saw that I said, “Time to get out of here.” So I moved to Maplewood, N.J. Made my living as a plumber. I had to wait five years. You had to be a U.S. citizen to get a plumber license. Maplewood is where we lived until I retired in 1986. I was living on a street with only policemen and firemen. I was the only Jew. At first they didn’t like it. But when they had trouble with the plumbing, they called me, and I helped them a lot, and then they liked me.Q: What is your message for the future generations?

When I came back to Poland after the war, all the big cities were flatten and bombarded. Even Breslau was flattened. Not a single house. It was a very big city. The Jewish quarter was four blocks—not a thing broken—this was a puzzle except the Jewish center. Why? When I was in Lodz, the first day the Germans came, the shul, the reform shul, they destroyed it the first day. In Breslau, not a window broken? Why? I don’t want to ever see cities flatten again. I hope Trump will manage it without flattening the world. They have the power to turn the world to ashes. Let’s hope they don’t. -

HISTORICAL NOTES:

Bialystok and Battle of Breslau

According to the terms of the German-Soviet Pact of 1939, Bialystok, a city in northeastern Poland, was assigned to the Soviet zone of occupation. Soviet forces entered Bialystok in September 1939, and held it until the German army occupied the city in June 1941 following the German invasion of the Soviet Union. In the early days of the German occupation, Einsatzgruppe (mobile killing unit) detachments and Order Police battalions rounded up and killed thousands of Jews in Bialystok. Establishment of a Ghetto in Bialystok: In August 1941, the Germans ordered the establishment of a ghetto in Bialystok. About 50,000 Jews from the city and the surrounding region were confined in a small area of Bialystok city. The ghetto had two sections, divided by the Biala River. Most Jews in the Bialystok ghetto worked in forced-labor projects, primarily in large textile factories located within the ghetto boundaries. The Germans also sometimes used Jews in forced-labor projects outside the ghetto.

The Battle of Breslau, also known as the Siege of Breslau, was a three-month-long siege of the city of Breslau in Lower Silesia, Germany (post-war Wrocław, Poland), lasting to the end of World War II in Europe.From 13 February 1945 to 6 May 1945, German troops in Breslau were besieged by the Soviet forces which encircled the city as part of the Lower Silesian Offensive Operation. The German garrison’s surrender on 6 May was followed by the surrender of all German forces two days after the battle.

-

Sources and Credits:

Credits:

SSBJCC Survivor Registry Interview, December 2, 2016 and May 15 2017 by Nancy Gorrell; Brief Biography by Nancy Gorrell; Digital historic and family photographs donated by Jacob Weinglass.