- Local Survivor registry

- MATT YOSAFAT

- Local Survivor registry

- MATT YOSAFAT

Survivor Profile

MATT

YOSAFAT

(1936 - 2021)

PRE-WAR NAME:

MATT YOSAFAT

MATT YOSAFAT

PLACE OF BIRTH:

KATERINI, GREECE

KATERINI, GREECE

DATE OF BIRTH:

AUGUST 8, 1936

AUGUST 8, 1936

LOCATION(s) BEFORE THE WAR:

KATERINI

KATERINI

LOCATION(s) DURING THE WAR:

SKOUTERNA VILLAGE, CAVE, LOG CABIN, GAVROU MITSOU VILLAGE, KALIVIA HARADRAS VILLAGE, TOHOVA VILLAGE (MARCH 30, 1943 - AUGUST 15, 1944)

SKOUTERNA VILLAGE, CAVE, LOG CABIN, GAVROU MITSOU VILLAGE, KALIVIA HARADRAS VILLAGE, TOHOVA VILLAGE (MARCH 30, 1943 - AUGUST 15, 1944)

STATUS:

CHILD SURVIVOR, REFUGEE

CHILD SURVIVOR, REFUGEE

RELATED PERSON(S):

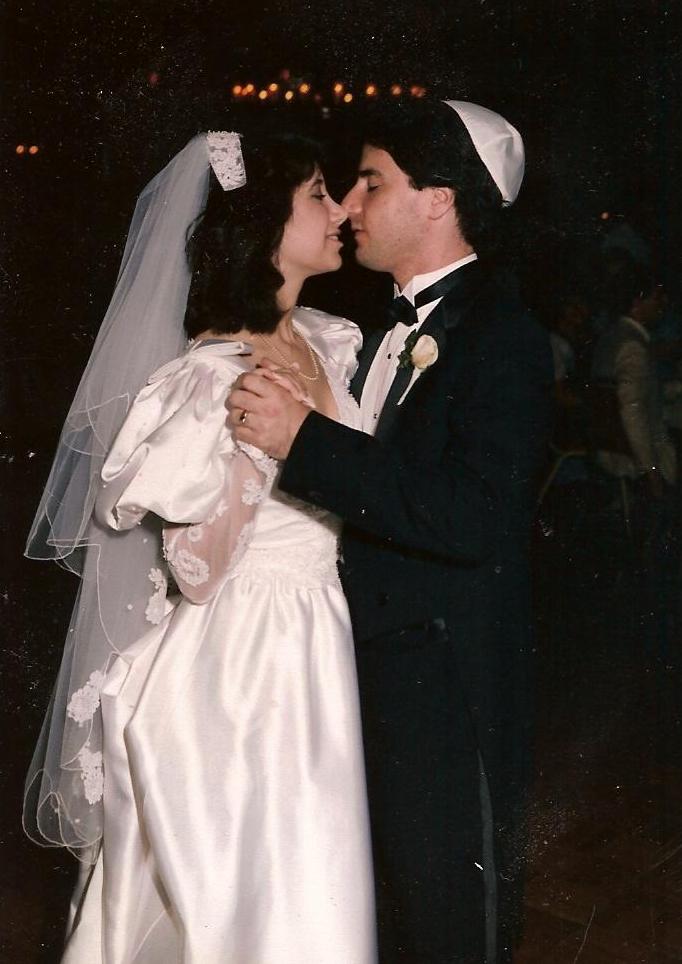

ANNELIESE YOSAFAT - Spouse,

WALTER A. YOSAFAT - Son,

DENISE YOSAFAT - Daughter-in-law,

LYNNETTE T. KOHEL - Daughter,

DEBBIE E. LEMPERT - Daughter

-

BIOGRAPHY BY NANCY GORRELL

Matt Yosafat was born in Katerini, Greece, on August 8, 1936, the only child of his father, David, a tinsmith, and his mother, Lena, a housewife. In his interview he describes Katerini as a “small, quaint, quiet” town, “a good place for a Jewish family to settle in.” He grew up among the ten, closely-knit Separdic Jewish families of Katerini, all closely related. “Life was good until World War II touched us, first by Mussolini attacking Greece, and then the Nazis following him. On March 30, 1943, all ten Jewish families fled together from Katerini in horse drawn wagons to avoid certain deportation.

From that time until liberation, Matt, a young child at the time, and his “extended” family hid in local villages and farms, in an above ground cave, in a log cabin, and in a mud hut, always seeking shelter and braving the elements of outdoor living while avoiding detection and capture from Nazi patrols. They hid for six weeks with 15 others in an above ground cave where they had little food or means of survival. Another time the family hid in a chicken coop, only to succumb to chicken lice. Later they hid in a vacant stable for a month, only to have to give it up to the farmer’s horse and cow. Matt spent some time in a tobacco barn where the woman who owned it made a storage-shed over the stable available for his family.

During that winter, Matt was able to go to a one-room schoolhouse. This was in Kalivia Haradras, where the mayor of the town, an acquaintance of Matt’s father, tried to protect them, but nevertheless, the family lived in constant fear of discovery. Matt recalls, “There were always people ready to turn us in.” Eventually, the ten families had to disperse “because the people said it’s not good to stay together because if one gets caught everybody gets caught.”

In the spring of 1944, Matt and his family ended up in Tohova. Matt was not quite nine years old. The Nazis, realizing they were losing the war, began to withdraw, and Matt was able to go stay with an uncle. Liberation came in August 1944. Matt recalls, “The whole family came back to Katerini. There was a big parade and jubilation. But then we came back to nothing. Everything was confiscated, our homes, my father’s shop.” Everyone in Matt’s family survived except one great uncle. Matt’s father had a brother and two sisters in the United States that came over at the turn of the century. “For a lot of people that was a dream in the sky. If you were Jewish and you wanted to go, HIAS was willing to fund it.”

Matt, his mother and father and younger twin brother and sister, left for New York City on October 23, 1951. They spent ten days in the Bronx with his sister and then settled in Cincinnati, where Jewish Family Service had made all the arrangements. Matt says, “It took courage to do what my father did. My father didn’t have the language and he only knew a trade and we packed up and came to a country we knew nothing about. My father wanted something better for his family.”

Matt passed suddenly at the age of 85 on December 7, 2021.

Editor’s Notes:

Refer to Matt’s Video Testimony in Related Media and in Gallery (on website toolbar)

Refer to Related Textual Material to view Matt and Anneliese’s Journey to Greece (p.3)

Refer to Historical Notes Below for Salonika and Jews of Greece.

Refer to Voices of the Descendants to read Walter Yosafat’s Registry

-

SURVIVOR INTERVIEW:

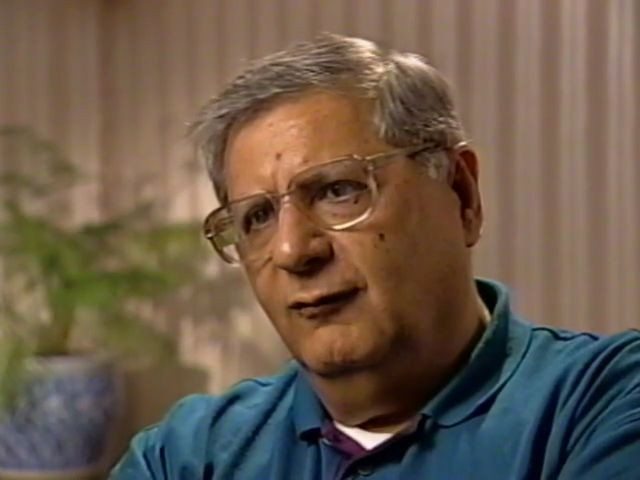

INTERVIEW WITH MATT YOSAFAT

Date: May 21, 2017

Location: Walter Yosafat Residence, Bridgewater, New Jersey

Interviewer: Nancy Gorrell

We gratefully acknowledge permission from the Yosafat family and the Shoah Foundation for use of audio material transcribed from Matt Yosafat’s Shoah Visual History incorporated in parts of this interview (Joan Centa, Interviewer, December 18, 1995).

Q: Describe your family background.

I was born in Katerini, Greece on August 8, 1936. My father, David, and his younger brother were business partners, tinsmiths. They owned a tinker shop, and they manufactured things out of tin—measuring cups, buckets, sprinklers, wood burning stoves—anything. My mother, Lena, had two younger brothers. She was born in Katerini as well. She was a housewife and homemaker. My father was also born in Katerini.Q: What was Katerini like when you were a child?

It was a small town probably 12,000 people—small, quaint and quiet—a good place for a Jewish family to settle in. It was mostly rural and there was a lot of farming. At the time there were ten Jewish families living there from about 1937-1943 when I was growing up.Q: What were your early childhood memories?

It was just my father, my mother and I. I had no brothers or sisters. We lived in a rented home. We had a Turkish landlady from whom I learned how to speak Turkish until we went into hiding. In the same town lived my mother’s parents and her two brothers. We also had my father’s mother who lived with us part of the year. Aunts, uncles and cousin were residents of Katerini. We were inter-related, all ten families. Life was good until WWII touched us, first by Mussolini attacking Greece, and then the Nazis following him.Q: What was your religious life like in Katerini? Were you observant?

My paternal grandfather was a rabbi. As long as there were enough Jews in Katerini, they would have services Friday evening and on Shabbat and on the holidays. Eventually, people left Katerini and moved to Salonika for more opportunities. In Katerini, people prayed in each other’s houses. We were Sephardic.Q: What was it like being Jewish in Katerini?

To be Jewish I knew was to be different. We had no synagogue. My father and the other men went to Salonika for the holidays to pray in the synagogue. Katerini did not have a synagogue. We celebrated the Sabbath mostly by having Friday night dinner and blessings at home. We could not close the business on both Saturday and Sunday. We couldn’t afford to be closed for two days.Q: Did you experience any anti-Semitism growing up?

Anti-Semitism in those days? Not so prior to the war. I had been well-prepared by my parents that I was Jewish. I didn’t feel much anti-Semitism until I went to school. There, I was told, I killed Jesus. I was five years old. My parents were raised among Christians, and there wasn’t much anti-Semitism, except my mother had a good girlfriend who wouldn’t talk to her on Good Friday. According to my mother, these two friends shared the most intimate things except she wouldn’t talk to her on Good Friday.Q: What was schooling like for you growing up?

Schooling? I started grade school in 1943. I barely had a chance to attend because we went into hiding. I was attending second grade when we went into hiding. It was either be shipped to concentration camps or go into hiding. So all the families in Katerini chose to run.Q: Do you remember when your family decided to go?

Yes, I remember very distinctly when the family decided to run. My father had a friend who worked at the telegram office and he received a wire and he told my father about its contents. He told him he could delay reporting to the Gestapo for 24 hrs. That gave us time to decide what to do. My father went home to tell my mother and me about it and found my mother and me going to visit his sister-in-law. He didn’t say anything. Then he proceeded to gather up all the other men to decide what to do. Once they decided we were going to run, then everyone went home trying to gather the families. My uncle went home and found me and his son playing on the street. He said, “Come into the house.” He was just my uncle and I didn’t give it much thought. Then, he said again, “You two come into the house!” It was the first time I had my uncle talked to me in that tone of voice. We knew it was serious. He said to my mother, “Better take Matt by the hand and get home.” So on the way home we met my father and she asked him, “How long have you known?” And he says, “About after lunch.” “Did you know when you stopped by earlier?” “Yeah,” he said, “ but I didn’t want to ruin your day.” That was an ironic thing. He let us go visit.Q: How did your family prepare for going into hiding?

My mother and father took some bed sheets to make a bundle. I asked my mother what to take. She said, “Take whatever you want.” I took a half dozen handkerchiefs. I always took handkerchiefs. That was the only thing I didn’t have handy when I was a kid. There were valuables I could have taken like watches and jewelry, but when you are under pressure, you don’t think of that. When you’re running for your life, you don’t give any thought to materialistic things.Q: Did you understand your family was in danger?

Unfortunately, yes. A lot of our relatives who lived in Salonika were being transported out of the country. It was being discussed openly that the Jews were being shipped off to concentration camps, and so when my father said we have to go, it sunk in real quick that our turn had come. I was a little over seven years old and this was March of 1943. Katerini was occupied by the Nazis. There were soldiers in our town. We lived right next door to the police station and the Gestapo set up its headquarters in the police station. Soldiers were all over the place. There was a curfew at night. The military presence was felt everywhere.Q: Did people in the town know you were Jewish?

Oh yes. The people in the town knew because first of all our name was Jewish, not a typical Greek name. My father and most of my relatives had been born and raised in Katerini, but the majority knew and all the businessmen and merchants knew we were Jewish.Q: Describe going into hiding. Where did you first go?

We went into hiding on March 30, 1943—all ten families. We took our bundles and met outside the city limits. One of the men got several horse drawn wagons for us to go away in. There was myself, my mother, my father, my mother’s parents and my mother’s two brothers, one of which was married, his wife and their one-year old daughter, my father’s brother and his wife and their three children. We stopped by a farm and we picked up two cousins of my mothers picking tobacco. There were other relatives but the memory is fuzzy. We didn’t get too far when we were stopped by the partisans. They wanted to know where we were going. We said we were Jewish and running for our lives. One was a friend of my father’s, and he let us stay in one town, Tohova, for the night. They dispersed us into various homes, and then the next morning, we just waited. We had to get clearance to go farther away from Katerini.Q: What happened next?

My father had idle time on his hands waiting. He was never one to make me anything with his hands. But he started to make me something. He was nervous so he decided to make me a whistle. In the process, he cut his finger. And this is one thing you don’t want to do if you’re going into hiding. It was an ironic thing. Of course the Greek people are very superstitious. It was an evil omen. This was very memorable.Q: Where did you go from Tohova?

From there we went to a small town known as Skouterna. They put us up for the weekend—the townspeople. My father had acquaintances in just about every small town around Katerini. So the townspeople put us up. After the weekend, they dispersed us in two or three homes. We spent maybe a week there. Then we were told we would have to leave because the Nazis were coming out on patrol.Q: Where did you go after Skouterna?

Then we went to an above ground cave. This cave was basically used by the sheperds in the early spring to house flock. Later the flocks would graze outside. The cave was large enough for about 10-15 people. I didn’t feel cramped, just cold and uncomfortable. We had to build a wooden fire and we had one pot for cooking and washing our clothes. We got our water from the river. We either had to walk or slide down the hill. I couldn’t carry the water containers. We always went in groups of two or three people. A friend of my maternal grandfather lived about a half hour from the cave and he brought us cornbread and hardboiled eggs. He also brought us a quarter of raw lamb. But we had no means of cooking it. We had nothing to eat with. Some people gave us odds and ends. We had to be careful not to make too much noise. We couldn’t even leave our blankets outside because of the Nazis might be on patrol. There were limitations about being outside. Don’t be too loud. After sundown we could go outdoors. We spent six weeks there.Q: Where did you go after hiding in the cave?

From there we moved to a log cabin. It was in the middle of nowhere. There was a farmer who owned the cabin and he owned a sawmill nearby. It was empty and he let us use it. We all spread some blankets over the wooden boards and that was housing. During the day, we spent time outdoors. We did mostly everything outdoors. There were no bathroom facilities. Nothing. We got water from the well. Not sure how much time we were there, probably two or three months. Soon winter was coming, and we would have to leave there and find warm shelter.Q: Where did you go after hiding in the log cabin?

From the log cabin we went to a small town known as Gavrou Mitsou. There were not too many people there. My mother’s father had an acquaintance there. Initially, we were all together. My parents found a place for us to live. It was a chicken coop. We got chicken lice. We had a terrible time. We spent sleepless nights itching. We had to bathe with Lysol and boil our clothes. Then we went to live in a vacant stable across town. One room was just a mud hut in the stable that the farmer had. He let us stay for a month until he needed it for his horse and cow.Q: How did you survive during the constant running and hiding?

We went to stay in the same cabin with my grandparents and my two uncles and my aunt and cousin. There, we were joined by one of my grandmother’s brothers and his wife. He came to town and knew how to make lye soap. The townspeople invited him. So he made it for them. We spent several months there, but then again we were forced to leave because the Nazis were coming. By this time my mother and aunt would disguise themselves as peasants, and they would go into Katerini and get tools, and they did jobs for the town’s people, and they paid us in lard, flour, cheese, bread, so food was not a problem by now. But being in constant fear was a problem. So we left again and went to another town known as Kalivia Haradras.Q: How did you survive in Kalivia Haradras?

We spent some time in a tobacco barn. Now it was getting winter. The woman who owned the barn made the storage shed over the stable available to us. When we were there, I was able to go to school; it was a one-room school. The same teacher taught the entire school. My father and grandfather set up a repair shop. The townspeople came and brought things to be repaired. My two uncles got brave and disguised themselves and went into town and picked up tools and medications. Of course, there was constant fear about whether they would come back. It was very traumatic. We didn’t know if they’d been caught. If they were caught, were they tortured? Did they tell where the rest of the family was? If things can go wrong, they will go wrong. You learn that real quickly. You learn to stay neutral. Don’t get into conflicts. This is a matter of life and death. The mayor of the town tried to protect us. He was an acquaintance of my fathers. There were always people ready to turn us in. When we were there, the Nazis came to the town on patrol. Whenever that happened, the men went into hiding in the woods. The Nazis once confronted the mayor, and they made him take them to where we were hiding. They were not SS but German soldiers. My father was still hiding in the woods. My uncles were inside hiding under blankets. My mother, grandmother and I were home and opened the door. My mother was the one who spoke. The soldiers said, “We heard there are some Jews living here.” My mother said, “We are refugees from Asia Minor.” They asked, “Where are the men?” A soldier pointed his gun at me and said, “You look like a Jewish boy.” We were sure that was the end. That evening they left. Nevertheless, we were very uneasy. We spent the remainder of the winter of 1943 there.Q: What happened to you in the spring of 1944?

That spring, the militia of an adjoining town ordered everyone in Kalivia Haradras to the town square. Trying to remain neutral, we didn’t go. They sent soldiers and got my mother, my grandfather and aunt. They said, “You’re coming with us.” I stayed behind with my grandmother. My grandfather said they took them back to Tohova. When my father and uncles got back from a work effort, it was night. They went to Tohova and found our family under the protection of the militia. They told my father to go back and get the rest of the family and come back to Tohova. Reluctantly, my father and uncle went back and got the rest of the family and then went to Tohova. By now the ten families had been dispersed in different directions because the people said it’s not good to stay together because if one gets caught everybody gets caught.

Q: Did your family stay in Tohova?

Yes. Tohova was about the next thing to being free and liberated. My father and his two brother-in-laws were able to set up shop, rent a place, repair old things, make new things. Living quarters were limited. There was also a battle going on between the militia and the partisans. The partisans thought the militia were traitors for accepting arms from the Nazis. Almost every night there was fighting going on. Eventually, when the Nazis realized they were losing the war, they began to withdraw. The militia began to lay down their arms. This was in the spring of 1944. I was not quite nine years old. When the Nazis finally left, I went to stay with an uncle.Q: Describe liberation for you and your family.

We were finally liberated in August 1944. The whole family came back to Katerini. There was a big parade and jubilation. But then, we came back to nothing. Everything had been confiscated, our homes, my father’s shop. The Nazis confiscated everything. Some people took things; there was some looting. My mother’s hope chest was looted. A lot of the neighbors felt so bad nobody would touch anything. The Nazis took everything. We were able to relocate my mother’s dresser and the basin and pitcher that used to sit on top of it. That’s about all.Q: Did everybody survive in your family?

Yes, except one great uncle. My mother had a cousin who was in his 20s. He was a maverick and did his own thing. When word got around that the Jews were being rounded up, they captured him and threw him in jail. He had a younger brother who was left behind when we went into hiding. This brother went to visit him in jail and they were both deported. The younger one perished. The older one returned to Salonika.Q: Describe how your family came to the United States?

My father had a brother and two sisters that came over to the United States at the turn of the century. Initially, we were going to go to Israel. Then the quota opened up to go to the United States and having a brother and sister in the US, for a lot of people that was a dream in the sky. If you were Jewish and you wanted to go, HIAS was willing to fund it. We were funded by HIAS. My mother and I and my father and my younger twin brother and sister left on Oct 8, 1951. We arrived in New York City October 23, 1951. We spent 10 days in New York because one of my father’s sisters lived in the Bronx, and she wanted us to stay. But we couldn’t stay because Jewish Family Service had made all the arrangements, and we had to go to Cincinnati. That’s where we settled. It took courage for my father to do what he did. My father didn’t have the language and he only knew a trade and we packed up and came to a country we knew nothing about. My father wanted something better for his family.Q: Did you ever go back to visit your hometown?

Yes. In 1980 I went back for the first time, and I took my mother because she had a brother still there. The house was still standing that we left. One of the few that had not been knocked down and renovated. Everything was still standing. I saw the house and the high school that my mother attended, the police station, the grade school that I attended, the church that I went with the scouts on Sundays was still there. My father’s shop had been converted to a store where they sold beauty products.Q: What message would you like to leave for future generations?

Never again. I would do anything in my power now to make sure this doesn’t happen again to anybody. People are persecuted because of the color of their skin or the slant of their eyes, but this was because of a crazy man. Also, study. Learn about the Holocaust. -

HISTORICAL NOTES:

Salonika was known as the Jerusalem of the Balkans and had a Jewish majority in Ottoman times. During Ottoman rule, the Jews of Greece thrived and coexisted peacefully with their neighbors for the most part. Under Ottoman control, Jews would experience a golden age that rivaled Muslim Spain. The Greek Jewish community consisted of two groups, the Sephardic Jews who were heirs of the Golden Age of Muslim Spain and Romaniot Jews, who were Hellenized and lived in the area for over 2,000 years.

However, this rich and ancient Jewish community dating back to antiquity was wiped out during the Holocaust. According to the Kehila Kadosha Ioannina Synagogue and Museum, out of all of the countries occupied by the Nazis, Greece lost the largest percentage of its Jewish population. A larger percentage of Greek Jews were selected to die at the death camps than that of any of the other Jewish communities. 87 percent of the Greek Jewish community, numbering between 60,000 and 70,000 souls, perished in the Holocaust. Most of them were murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

-

related textual material:

MATT AND ANNELIESE’S JOURNEY BACK TO GREECE, Summer 2000

OUR JOURNEY BACK TO GREECE

-

Sources and Credits:

Credits:

SSBJCC Survivor Registry Interview, May 27, 2017, Interviewer: Nancy Gorrell; Biography by Nancy Gorrell; Matthew Yosafat, Shoah Visual History, December 18, 1995, (The Shoah Foundation: Interviewer, Joan Centa). Digital historic and family photographs and documents donated by Matt Yosafat.

We gratefully acknowledge permission from the Yosafat family and The Shoah Foundation for audio material transcribed from Matthew Yosafat’s Shoah Visual History, December 18, 1995, Interviewer: Joan Centa.