- Local Survivor registry

- MAUD PEPER DAHME

- Local Survivor registry

- MAUD PEPER DAHME

Survivor Profile

MAUD

PEPER

DAHME

(1936-Present )

PRE-WAR NAME:

MAUD PEPER

MAUD PEPER

PLACE OF BIRTH:

AMERSFOORT, NETHERLANDS

AMERSFOORT, NETHERLANDS

DATE OF BIRTH:

JANUARY 24, 1936

JANUARY 24, 1936

LOCATION(s) BEFORE THE WAR:

AMERSFOORT, NETHERLANDS

AMERSFOORT, NETHERLANDS

LOCATION(s) DURING THE WAR:

OLDEBROEK AND ELBURG, THE NETHERLANDS

OLDEBROEK AND ELBURG, THE NETHERLANDS

STATUS:

HIDDEN CHILD, REFUGEE

HIDDEN CHILD, REFUGEE

RELATED PERSON(S):

HANS JOACHIM DAHME - Spouse (Deceased),

RANDALL DAHME - Son,

SUSAN DAHME - Daughter,

KAREN DAHME - Daughter,

AMY DAHME - Daughter,

9 Grandchildren - JORDAN, ZACHARY, TUCKER, NATALEE, HANNA, HOGAN, DECLAN, DONIVAN, CAMERON

-

extended BIOGRAPHY BY NANCY GORRELL

Adapted from Dahme, Chocolate, The Taste of Freedom: The Holocaust Memoir of a Hidden Dutch Child

Of the 1,600, 000 Jewish children who lived in Europe before WWII, only 100,000 survived the Holocaust. Most were hidden children, shuttered away in attics, convents or in villages and farms…Maud Dahme was one of the estimated 3,000 to 8,000 Jewish children from the Netherlands who were hidden and saved from the Nazi death camps by courageous Christians.

(Chocolate, The Taste of Freedom).

Maud’s story begins with her parents who were from two different countries, but luckily for her, met and married. Her father, Hartog, “Harry” Jacob Henri Peper, was born on January 5, 1913 in Hilversum, the Netherlands, near Amsterdam, and he was a Kohen. Her mother, Lilli Eschwege, an only child was born on December 31, 1911 in Saar Louis, so her first language was French. Her parents moved to Frankfurt Am Main, Germany, where her grandfather was a cantor. After they married in 1935, they moved to Amersfoort, in central Netherlands. Her father worked with her grandfather in the family restaurant business at the tram station. Maud was born on January 24, 1936, and she was named after her German grandmother. Her sister, Rita, was born two years later, February 23, 1938. After Kristallnacht (November 1938), her father went to Frankfurt to bring her German grandparents back to Amersfoort, thinking that the Netherlands, a country of tolerance, was a “safer” place to live. Maud doesn’t remember much of her childhood until the German invasion of 1940, when the Dutch government surrendered after four days of horrendous bombing. At that time, she was four and Rita was two.

After the Dutch invasion, the Germans took over all the military bases in and around her town. One of the first things they did was register the Jews of Amersfoort, who numbered about 731. In May 1940, the Jews of Amersfoort were subjected to numerous restrictions: forbidden to go to parks; forced to have a big “J” stamped on their identity cards; and restricted from restaurants. By 1942, Maud and all Jews were required to wear a star; restricted from public transportation, and all Jewish children were banned from public schools. Finally, Jews were restricted from hospitals and told they could not visit non-Jewish friends. A Dutch Nazi trustee was appointed to oversee their family restaurant. On August 16, 1942, all Jewish males between 18-45 were told to report for forced labor in Germany. All other Jews were to be deported by the Nazis on August 21, 1942, to Amsterdam. Then there were about 120 Amersfoort Jews left—the old and ill and those married to Christians. By May, the remaining Jews had been deported from Amersfoort to the Westerbork Transit Camp. From there, in the summer of 1943, most were deported to Sobibor Death camp. Most all of Maud’s family, except those who went into hiding, were deported and eventually murdered in the Sobibor Death Camp: her Dutch grandfather, Wolf; her German grandparents; and her aunt, uncle and cousins.

Maud’s immediate family was not deported. In July 1942 when the Amersfoort Jews received the “letter” from the Kommandant to pack their things, bring money and jewelry and leave their homes for the train station, her parents went to see a non-Jewish friend who was working with the Dutch resistance. He told them not to go, and that the resistance was gathering names of Christian families who would hide Jewish children. “We cannot tell you who your children will be hidden with. We cannot tell you where your children will be hidden. We cannot tell you anything because if you are caught and tortured, you will not be able to reveal anything. You have to decide tomorrow.” Maud’s parents discussed this “heart-wrenching proposal” and decided it would be the best thing to do. They told Maud and Rita, “We were going on a vacation to a farm for a few weeks.” They gave them their little bags and their father said, “We’ll see you in several weeks. Take good care of your sister, Maud.”

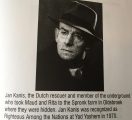

Maud and her sister left with the Jan Kanis family in July 1942. They were the first Jewish children in their home. They were given dinner and then put to bed. Maud recalls, “They woke us up in the middle of the night. We left their house around 4:00 am and walked through the woods, reaching the next town by daylight where we took a train.” Years later, Jan Kanis, their rescuer, would be recognized as Righteous among the Nations in Yad Vashem, the Israeli Holocaust museum in Jerusalem.

Jan Kanis left Maud and her sister on a farm in Oldebroek with Mr. and Mrs. Spronk, an elderly, childless couple. It was a very poor region; the farm had no running water or toilet. Mr. Spronk, Hendrik, was a deaf mute. The immediately were told about their new identities. They had to call the Spronks, aunt and uncle, Oom and Tante. Maud’s name was Marjie; Rita’s, Rika. They were homeless nieces now living with the Spronks because their family was bombed out of their city. “You are now Christian. You have to remember this! If you do not remember this correctly, the German soldiers will take you away.” They did not attend school but they did attend church and the cover story was drilled into them every “single day.” “Rita and I were now Onderduikers, literally, under divers or underground, the name given to Dutch people hiding from the Nazis.

Maud recalls with horror a roundup on October 3, 1944 when German soldiers arrive at widow Blaauw’s farm. She was hiding Maud’s teacher and other Jews. The Germans took them and the widow’s son and paraded them around town and then made them dig their own graves and then shot them. In February the bodies were discovered and transported to the transit Kamp Westerbork and buried. (Maud notes in her memoir that in 2001 a monument was erected and unveiled by town officials to the memory of the six Jews murdered on October 3, 1944).

Maud recalls some of the pleasures of living on the farm. “As city children, life on the farm was especially interesting…and aunt and uncle were very nice to us.” She recalls with sadness the passing of uncle Henrik, on January 20, 1944, from a heart attack just a few days before her eighth birthday. When uncle died, the underground sent word that Tante couldn’t keep the children because other relatives were coming to help Tante run the farm. She wrote a letter to her parents, now in hiding themselves, telling them that uncle has died. The underground delivered the letter to her parents. (Note: This letter is now in the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C.)

Through an underground tip, Maud and Rita were moved to Elburg, a fishing village in December 1944 for fear the Germans would be searching Tante’s farm. They were to stay with the Westerink family, Jakob, the husband, Henriette, his wife, and a 20-year-old daughter, Johanna or “Jo”. Again they had to change their names. Maud’s was Marie. Maud and her sister were “refugee relatives, their houses destroyed by bombings.” There was little to eat. The whole town was starving. The apartment was small—living room, kitchen and two bedrooms. There was no electricity or gas during the war. Nor were there radios, newspapers or teachers or schools. It was the Hunger Winter; the Dutch all over the Netherlands were starving. They were in constant danger, afraid to go outside and always hungry. “What people remember most about that winter besides the cold, hunger and darkness, is eating tulip bulbs”. By May 5, 1945, the Netherlands was liberated by the Allied forces and food supplies were arriving daily.

Maud describes the “taste of freedom”. The Allies had given the Dutch underground the honor of entering Elburg first followed by Canadian tanks. On April 19, 1945, Maud was liberated. She recalls, “To suddenly realize that we were free! I can’t fully describe our feelings of joy. People were hugging and kissing…The soldiers threw us chocolate bars; I had no idea what these were…Jo broke off a piece and shoved it into my mouth…To this day I love chocolate.”

Maud’s parents survived the war hiding in the other end of Amersfoort in an apartment of Christian friends, Hennie and Lies Lippinghof, above their Wilco Ford dealership. The underground knew where her parents were but they had no idea where their children were. Maud’s father never went outside for the whole three years they were in hiding. After Elburg was liberated, Maud and her sister returned to Oldebroek to wait for their reunion with their parents. Maud was nine years old and a “very devout Christian” by this time. When her parents arrived on the farm, Maud recalls, “Rita and I did not recognize them. Rita and I hid behind Tannie.” Her parents decided to stay on the farm for a while to get reacquainted. Maud recalls that all the time they were in hiding, “she had been Rita’s mother, so I negotiated our future.” At first, Maud said, “No”; we wouldn’t go home with our parents.” After a while, Maud made a bargain with her parents. They would go home with them; however, if they didn’t like it, they would come back and live with Tannie. Her parents agreed.

Maud’s family finally reunited and returned to Amersfoort to begin to rebuild their lives. It was a traumatic time for Maud. They waited for their loved ones to return, only to get the news they had been sent to Sobibor. Rita and Maud went back to their former names. They had an accent, had to re-learn Dutch and become accustomed to modern clothes and giving up the traditional Dutch clothing and wooden shoes. By the fall of 1945, Maud suffered what was then called a “nervous breakdown.” She was put on bed rest and lost six months of school. In the spring of 1946, the Canadian Red Cross sent ill children out of the country for rehabilitation. Rita went to Switzerland for her asthma and Maud was sent to England. She spent four months rehabilitating with other Dutch youth and with a Jewish family, the Abels, who introduced her to synagogue observance and holidays. By the fall of 1947, Maud’s parents decided to move to Amsterdam where her father had his business. Maud caught up to the 5th grade and was attending school. In 1949 a letter came from the Dutch Red Cross confirming the deaths of Maud’s maternal grandparents and her father’s family in Sobibor Death Camp.

Maud’s parents made the decision to emigrate from the Netherlands. Some of her mother’s relatives (Dr. Samuel Eschwege and Dr. Leo Hess) had left Germany in the early 1930s, and they immigrated to the United States. They were living in New York City and were eager to sponsor Maud’s family. Tannie passed away on January 1, 1950 and Maud’s family left for the U.S. in April 1950. They arrived at the Holland pier in Hoboken on April 24, 1950 with their relatives there to greet them. They first settled in New York City in a rooming house. Maud attended New York City schools. It was a difficult adjustment for Maud at first, learning a new language and catching up in grade school. But by January 1951, after her parents moved to Forest Hills, she began attending Forest Hills High School. With hard work, Maud graduated high school in 1954 with students her own age. Her father bought into a food business and eventually the family moved to Palisades Park, New Jersey. After he sold the business, her father worked for a spice company and was a travelling salesman for the northeast.

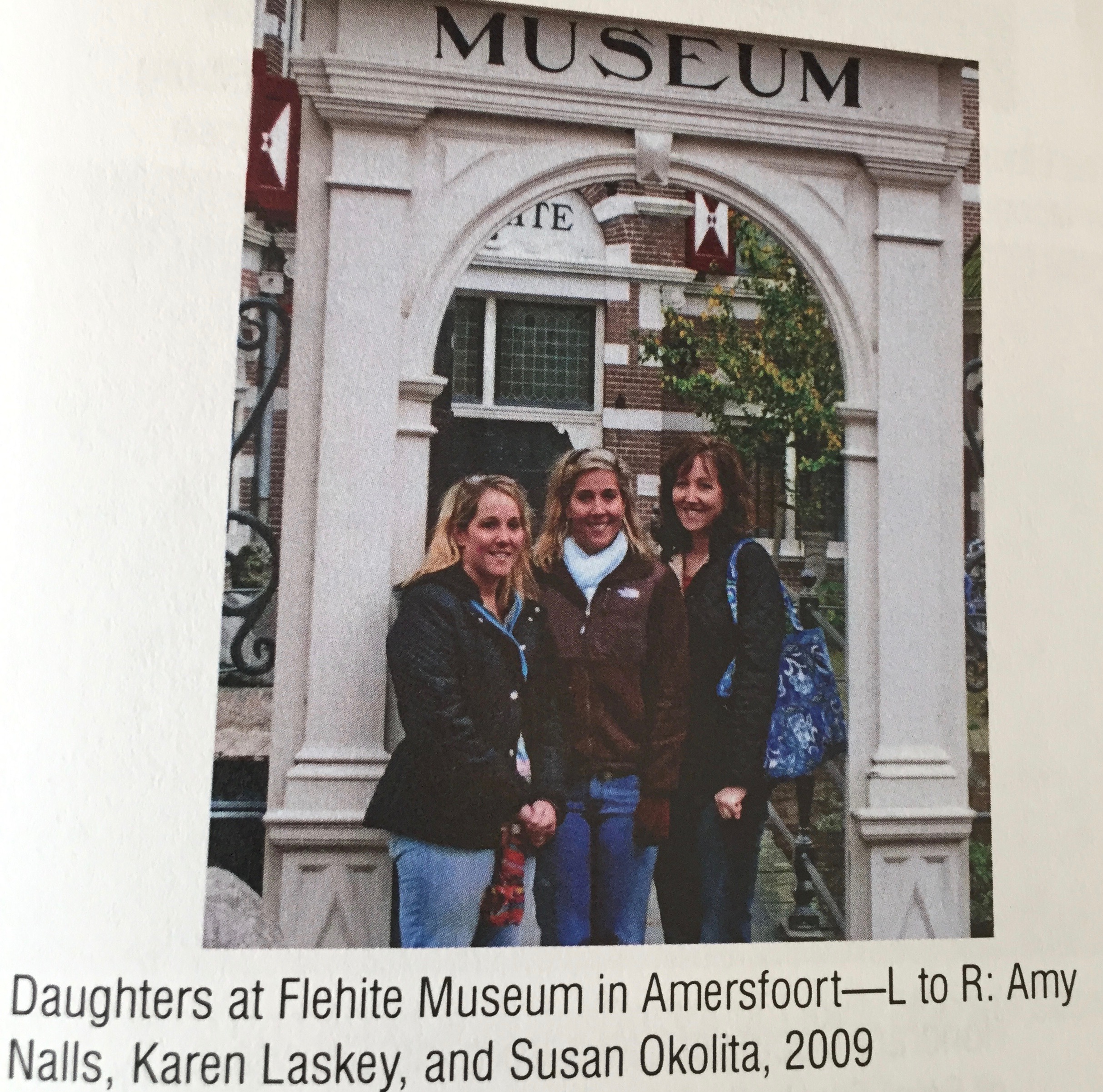

Maud went to work after graduating high school. In 1954 she secured a position with Pan American World Airlines, where she met her future husband, Hans Dahme. They were married on July 15, 1957 and have four children, Randall, Susan, and the twins, Karen and Amy. They have nine grandchildren: Jordan, Zachary, Tucker, Natalee, Hanna, Hogan, Declan, Donivan, and Cameron. Hans passed away on January 29, 2001 of an infection in the lining of his heart.

Maud has devoted her life to Holocaust education for both teachers and students and public education in the State of New Jersey. Her most notable volunteer accomplishments are: 24 years as a member of the New Jersey State Board of Education, President of the National Association of School Boards (1995), seven years on her local North Hunterdon School Board, chair of the Interstate Migrant Education Council, and long time member of the New Jersey Commission on Holocaust Education.

In 2006, Maud’s life as a hidden child received national telling when a one-hour documentary, The Hidden Child, was broadcast on PBS. Matt Schuman, in “Beyond Hate” describes the film as “a gripping tale of survival, The Hidden Child tells the story of a six-year-old girl and her sister separated from their parents, dodging bullets, lying for survival, and relying on the compassion of strangers who risked their lives to save Jewish children.”

Editor’s Notes:

Refer to Related Media for photo of Janis Kanis and Historical Notes for Jan Kanis.

Refer to Related Textual Materials for Selected Book Chapters of Chocolate the Taste of Freedom: The Holocaust Memoir of a Hidden Dutch Child.

Refer to Historical Notes below for Hidden Children history.

-

SURVIVOR INTERVIEW:

Refer to Extended Biography Above and Selected Book Chapters in Related Textual Materials.

-

HISTORICAL NOTES:

HIDDEN CHILDREN:

Of the 1,600, 000 Jewish children who lived in Europe before WWII, only 100,000 survived the Holocaust. Most were hidden children, shuttered away in attics, convents or in villages and farms…Maud Dahme was one of the estimated 3,000 to 8,000 Jewish children from the Netherlands who were hidden and saved from the Nazi death camps by courageous Christians (from Chocolate, The Taste of Freedom).

RIGHTEOUS AMONG THE NATIONS:

(Those who Saved Maud Peper)

Jan Kanis and his wife Nel Petronella were honored as Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem in 1970

The Westerinks and Spronks were honored as Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem in 2014 (Refer to Photographs in Related Media)

-

related textual material:

DAHME CH. 1 & 2; CHOCOLATE

DAHME CH. 3-6; CHOCOLATE

DAHME CH. 7-12; CHOCOLATE

DAHME CH. 13-20; CHOCOLATE

-

Sources and Credits:

Credits:

Extended Biography by Nancy Gorrell, adapted from Maud Dahme, Chocolate, The Taste of Freedom: The Holocaust Memoir of a Hidden Dutch Child (CMTEQ Publishing, 2015) and donation of digital, historic and family photographs therein.

The SSBJCC Holocaust Memorial and Education Center gratefully acknowledges permission received from Maud Dahme and Stockton University Holocaust Resource Center and Graphics Production to reproduce material and selected chapters from Chocolate, The Taste of Freedom: The Holocaust Memoir of a Hidden Dutch Child . The Center also gratefully acknowledges donation by Maud Dahme of copies of her memoir.