- Local Survivor registry

- EDITH KORNBLUTH

- Local Survivor registry

- EDITH KORNBLUTH

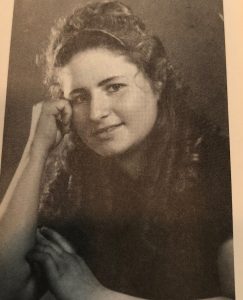

Survivor Profile

EDITH

KORNBLUTH

(1929-2005)

PRE-WAR NAME:

FROFLICH

FROFLICH

PLACE OF BIRTH:

KUPNO, POLAND

KUPNO, POLAND

DATE OF BIRTH:

DECEMBER 15, 1929

DECEMBER 15, 1929

LOCATION(s) BEFORE THE WAR:

KUPNO, POLAND; POREMBY KUPIENSKIE AND KOLBUSZOWA, POLAND

KUPNO, POLAND; POREMBY KUPIENSKIE AND KOLBUSZOWA, POLAND

LOCATION(s) DURING THE WAR:

KUPNO; POREMBY KUPIENSKIE; GHETTO GLOGOW; POLISH FORESTS; RZESZOW, POLAND

KUPNO; POREMBY KUPIENSKIE; GHETTO GLOGOW; POLISH FORESTS; RZESZOW, POLAND

STATUS:

CHILD SURVIVOR

CHILD SURVIVOR

RELATED PERSON(S):

WILLIAM KORNBLUTH - Spouse (Deceased),

PHIL KORNBLUTH - Son,

RENEE KORNBLUTH - Daughter,

JEFF KORNBLUTH - Grandson,

KIM KORNBLUTH - Granddaughter

-

EXTENDED BIOGRAPHY BY NANCY GORRELL

BIOGRAPHY OF EDITH KORNBLUTH ADAPTED BY NANCY GORRELL FROM SENTENCED TO REMEMBER, CHAPTERS 1, “EDITH’S STORY” AND CHAPTER 15, “EDITH EMIGATES” BY WILLIAM KORNBLUTH

Edith was born in 1929 in Kupno, Poland to a large prosperous extended family. Her mother, Feiga had eight siblings. Feiga’s parents, Edith’s maternal grandparents, Nuchem and Grandmother Pearl operated a farm and owned an inn in the village of Kupno, near the town of Kolbuszowa. The village of Kupno had little opportunity so two of Feiga’s sisters, Gussie and Lena emigrated to America. Grandfather Nuchem was a cautious man and didn’t want to leave an established life in Poland for an uncertain future. After Edith’s aunts left for America, her mother to be, Feiga and her uncle Avrum were born. Feiga grew into a beautiful young lady. Edith’s parents met at a wedding of mutual friends and relatives. After a brief courtship, they married. Pinia was a graduate of business school, but had no money to start a business, so they moved in with Feiga’s parents. Shortly thereafter, Edith was born. Three years later, Pinia’s education paid off and he got a job as assistant administrator of a large estate owned by seven brothers who owned thousands of acres of forests. Edith and her family moved out of the grandparent’s residence to Poremby Kupienskie and their new home. There, Pinia was held in high esteem and his second title in Poremby Kupienskie was “wise Pinia.” He was also referred to as the “nice Jew.” Edith recalls, “My parents’ happiness hit its height three years later” after her sister, Chavcia was born when her brother, Goetzaly was born. She describes those days as joyful “kisses, affection and love” from her parents and extended, close knit family. Edith attended school in the nearby town of Kolbuszowa during the week and came home on weekends. “I always had mixed feelings leaving that lovely house with its large warm kitchen.” But “luckily I was an extrovert who made friends easily and adjusted quickly to new environments. I had little idea when I left with my father on those cold Poland Sunday afternoons that these very character traits would save my life.”

In 1937 tragedy struck Edith’s happy family and life. Her brother Goetzaly died suddenly of diphtheria at age three. “Nothing ever seemed the same after my brother’s passing. His death was like an omen.” Although her parents tried to keep the rising anti-Semitic atmosphere from Edith, she was well aware of the “gloom and doom” around her. In Kolbuszowa “anti-Semitism was a raging disease.” In 1939 when the Germans invaded Poland, the Nuremberg laws were instituted. “School was out of the question for me.” The estate Edith’s father worked for was confiscated and Pinia was kept on to work for the Germans. When the “German occupiers found out we were well off, they paid us a visit.” They beat Edith’s father, ransacked the house, and confiscated “stuff” that was not well hidden. “For a long time we lived in fear of these visits.” At the end of 1940, Edith’s family was order to leave their house. They moved into a two-room apartment with a “local peasant family.” “Wise Pinia had taken precautions, however, and smuggled our best valuables out of the house.” He left them with a nearby “friend,” Pastula. Edith describes this “as a clever ruse at the time.” But in fact, it was this “act of deception that sealed his death.” Years later, Pastula would betray Edith’s parents causing their deaths right before the end of the war. Six months after moving to the apartment, Edith’s family was ordered to ghetto Glogow. They shared a single room with another family, the Klugers. Pinia had to report daily for forced labor.

Rumors circulated that ghetto Glogow would soon be liquidated. Edith’s father contacted a good gentile friend, Orzech, who had worked for him. Orzech promised to shelter the family until they could find another solution. At the Orzechs, Edith learned from Orzech’s daughter how to say the Christian prayers in Polish. Edith recalls: “If any prayers have ever saved a life, those saved mine.” A first Edith’s family slept in the house and then in Orzech’s barn. Orzech decision took courage but he was scared for the lives of his family. After a few weeks, Edith’s family “took up full time residence in the forest.” One week after their departure, the Glogow ghetto was liquidated. Hiding in the forest was brutal and dangerous for Edith’s family. There were Jew hunters, fugitives from the law, “but just as dangerous the “Polish Home Army, units of Poles who were supposed to be fighting Germans. It was easier and more lucrative to attack defenseless Jews than well-armed Germans. Besides, they hated Jews and Germans equally.” Edith describes nearby peasants joining the Polish Home Army attacking, robbing and murdering Jews and other times delivering them to the Gestapo for bounty.

As a result of the hardships and dangers of hiding out in the Polish forests, Edith’s parents decided to send her out of the forest to live on her own passing as a gentile: “Child, we have heard that some Jewish youngsters live on the outside as gentiles. Do you think you can do it?” Edith was only 11 at the time. She was stunned at the notion of being separated from her parents. Her sister, Chavcia was only eight. Edith was frightened but knew they were right. “I was mature, blond, and didn’t look Jewish.” She even knew her Christian prayers. They tearfully separated one chilly fall day in 1942. Edith bravely left her family and walked down the road into a village asking peasants if anyone needed a girl to take care of children. Her parents had concocted a story for her to tell: her father was gone, most likely killed in the war and her widowed mother had five young children. She couldn’t support all of the family. It worked and the peasants referred her to a family in Rzeszow who needed help with two little children. Edith gave her name as Stacia Orzech, the daughter of the good man Orzech. He would cover for her if there were any danger her parents thought. For two weeks Edith stayed with the peasants and worked in the fields, and then the Depas from Rzeszow came to get her (Refer to photo in Related Media).

So began Edith’s life passing as a gentile while her family struggled to stay alive in the forests during the height of the Final Solution. Her life with the Depas was “hard.” They needed and wanted “cheap help.” The father was out of work and the mother was the main breadwinner. They were living a meager existence. Edith worked day and night. But she was eating and she was safe. After six months, she asked for time off to visit her family. They agreed. First she went to the Orzechs to get information. Her parents were alive. Orzech knew there constantly changing locations because he brought them food. He agreed to take Edith to them. When she saw her parents “her heart sank.” Her mother only in her thirties looked like an old woman. Her father was gaunt and grim. Chavcia was nowhere in sight. The story of Chavcia’s death was horrific. There was a raid organized by local peasants. In the chaos, Chavcia ran off with one of the aunts. They lost their sense of direction and ended up on a road where peasants picked them up and delivered them to the Gestapo. They were held in a cellar and a week later, shot by the Gestapo. Chavcia was only nine years old. Edith was heartbroken and did not want to go back to the Depas. “Life no longer made sense to me, and I had no desire to go on living…What ever my parents’ fate would be, I wanted to share it.” Edith’s parents persuaded her to go back with the help of Orzech and Stacia, his daughter. Her parents said: “There is little hope for us, child, but you will survive.” Edith finally agreed to go despite many tears and embraces. Two months later she again asked for a leave to visit her parents. This time it was the middle of winter. They were staying in another peasant’s barn. Her parents looked worse than her first visit. They were dressed in rags, freezing and starved. After three days, Edith had to leave. This time the Depas sent her “on loan” to help her pregnant sister. After eight or nine months Edith returned and asked to “visit her parents” again. This time she found out to her shock that her parent’s were not alive. The story was tragic beyond words. Now that the war was nearing its end, Pastula was afraid that Feiga and Pinia would try to reclaim their belongs. He was not about to part with the “nice furniture, silver candelabra, and other valuables given to him for safekeeping. He had been keeping tabs on Edith’s parents hiding places and reported their location to the Gestapo. They were hiding in a local peasants barn. “They were both shot on the spot.”

Editor’s Note:

The story continues in Chapter 15, “Edith Emigrates” from Sentenced to Remember

After hearing the news of her parent’s deaths from Preneta, Edith says, “I wanted to die too.” She stayed with Preneta a few days in a state of shock and then returned to the Depas, “emotionally numb.” Edith sums it up this way: “My mother and father, 34 and 37 years old respectively, died when the war was nearly finished. They had overcome inhumane suffering in the woods, dodging raid, enduring cold and hunger. Less than twelve weeks before liberation, their lives came to an abrupt end, all because of the greed of a peasant.” The brutal irony was that Pastula did not need to inform. Edith’s father planned to leave him “all the goods that he had held during the war” and in addition, he planned to reward him handsomely for protecting them. When the war ended, Edith had a neighbor tell the Depas she was Jewish. “Mrs Depa was furious.” Edith never went back to them. Instead she returned to Poremby Kupienskie, her old house and Mrs. Preneta who greeted her warmly. Edith was alone in the world. She decided to stay with Mrs. Preneta for a while. She was only 15. “I wanted and education” and after pretending to be Christian for three years, “I wanted to see what it was like to be Jewish again.” After two weeks, a distant cousin of Edith’s turned up, Martin Rosenberg who had heard about her return. Cousin Martin took her to Kolbuszowa where she went to the town hall to get her identity papers. Edith’s ultimate goal was to move west until “I got to America.” She knew of her mother’s sisters in America. She made her way to Austria, and there is Salzburg she stayed in a D.P. Camp briefly. She encountered hatred and anti-Semitism from the Austrians and couldn’t wait to leave. It took her three weeks before she managed to get a “semi-illegal pass to Germany” which allowed her to move to Lansberg Am Lech and a D.P. camp in Bavaria. Since her singular goal was to reach America, she learned of the easiest way—to live in an orphanage for surviving Jewish children in Prien, Bavaria. It worked. In early August 1947, Edith and a group of other orphans were moved to Funk Kasserne in Munich to be processed for emigration. In one month, Edith and others were shipped to Bremerhaffen, a port in northern Germany. From there they boarded a former U.S. troop ship, the Ernie Pyle. Fourteen days later she arrived in Manhattan where two-dozen relatives greeted her as the “miracle youngster who survived Hitler’s Gehanna in Europe.”

Editor’s Note:

The remainder of Edith’s story continues with William’s story in William’s Registry. Refer to William’s Registry and Biography and/or his Complete Memoir in Related Textual Materials: Chapter 16 to End.

Refer to Historical Notes Below on Rzeszow and Glogow Ghettos and Glogow Monument to Massacres

-

SURVIVOR INTERVIEW:

REFER TO THE CHAPTERS ON EDITH IN WILLIAM KORNBLUTH’S MEMOIR IN RELATED TEXTUAL MATERIAL BELOW, SPECIFICALLY CHAPTERS 1 AND 15.

-

HISTORICAL NOTES:

GLOGOW GHETTO AND MONUMENT IN MEMORY OF THOSE WHO PERISHED

Photo of the Głogów Monument

Between 1942-1944 approximately 6.000 Jews from Blazowa, Czudec, Głogów, Kolbuszowa, Łańcut, Lezajsk, Majdan, Niebylec, Sêdziszów Małopolski, Sokołów Małopolski, Strzyzow, Tyczyn, Rzeszów and other shtetlach nearby, were taken from the Rzeszów Ghetto to the Głogów forest, just N of Rzeszów and killed by the Nazis.

The largest number were killed between July 7-18 1942. The victims were ordered to undress and stand before the gaping pits and were mowed down by machine guns. Many fell into these mass graves while still alive. The Nazis poured sand over the mass graves and levelled them with bulldozers. Peasants living in the vicinity reported hearing cries and moans for several days after the massacre.

This monument was built in memory of the Jews who lie in these mass graves.

Submitted by Susana Leistner Bloch. Photo was taken during her visit October 1999

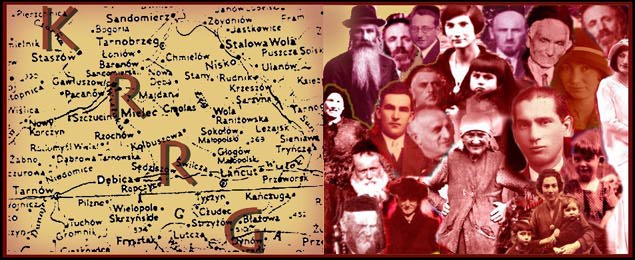

© Copyright 2002 Kolbuszowa Region Research Group. All rights reserved.

Compiled by Susana Leistner Bloch and Neil Emmer

-

related textual material:

EDITH KORNBLUTH'S STORY BY WILLIAM KORNBLUTH CHAPTERS 1 AND 15 TO END

-

Sources and Credits:

Credits:

William Kornbluth, Chapter 1, “Edith’s Story,” and Chapter 15, “Edith Emigrates,” in Sentenced to Remember: My Legacy of Life in Pre-1939 Poland and 68 Months of Nazi Occupation (Leigh University Press, 1994); Extended Biography by Nancy Gorrell from Sentenced to Remember;

The SSBJCC Holocaust Memorial and Education Center gratefully acknowledges the donation of hardcover copies and an electronic copy of Sentenced to Remember donated by Phil Kornbluth and digital and historic family photographs and documents.