- Local Survivor registry

- WILLIAM KORNBLUTH

- Local Survivor registry

- WILLIAM KORNBLUTH

Survivor Profile

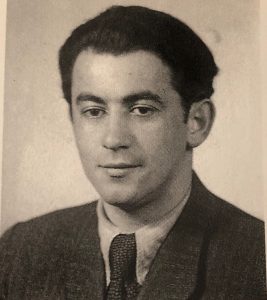

WILLIAM

KORNBLUTH

(1922-2005)

PRE-WAR NAME:

VOVEK KORNBLUTH

VOVEK KORNBLUTH

PLACE OF BIRTH:

TARNOW, POLAND

TARNOW, POLAND

DATE OF BIRTH:

JANUARY 8, 1922

JANUARY 8, 1922

LOCATION(s) BEFORE THE WAR:

TARNOW , POLAND

TARNOW , POLAND

LOCATION(s) DURING THE WAR:

TARNOW GHETTO; PLASZOW, POLAND; MAUTHAUSEN, ST. VALENTIN AND EBENSEE CONCENTRATION CAMPS, AUSTRIA

TARNOW GHETTO; PLASZOW, POLAND; MAUTHAUSEN, ST. VALENTIN AND EBENSEE CONCENTRATION CAMPS, AUSTRIA

STATUS:

SURVIVOR

SURVIVOR

RELATED PERSON(S):

EDITH KORNBLUTH - Spouse (Deceased),

PHIL KORNBLUTH - Son,

JEFF KORNBLUTH - Grandson,

KIM KORNBLUTH - Granddaughter,

RENEE KORNBLUTH - Daughter,

NATHAN KORNBLUTH BROTHER (Deceased),

SIMON KORNBLUTH BROTHER (Deceased),

BRONKA KORNBLUTH SISTER (Deceased),

KLARA KORNBLUTH SISTER

-

BIOGRAPHY BY NANCY GORRELL

ADAPTED FROM SENTENCED TO REMEMBER BY WILLIAM KORNBLUTH (1994)

Sentenced to Remember: My Legacy of Life in Pre-1939 Poland and Sixty-Eight Months of Nazi Occupation

For most of my adult life I was a clam. Until 1983 I told very few people about my past experiences, about the horrors that I and my family lived through. My children Renee and Phil know little of my story; I couldn’t speak of the unspeakable with them or with anyone who did not share a similar background.

A Message to my Children:

The thought of leaving this planet with my story and your mother’s story untold makes me shudder. Every human being…needs to know about his roots, where he came from. In your case, I strongly feel you also need to know what your parents had to endure in their lifetime…For some time I have been contemplating the idea of putting down on paper what is so difficult to tell you face to face…My advancing years shout out to me: ‘now or never! This is your last chance!’

William (Vovek) Kornbluth was born in 1922 in Tarnow, Poland to Sumer and Chana. Sumer, a deeply religious and a devoted Torah scholar was eight years Chana’s senior. He was not of the modern world, studied all the time, and struggled to provide for his family. Chana who protested the marriage came from a large, prosperous family. Her father, Srul was in the timber business. She was only a girl of 17 in 1909 and had no say in the matter of Srul’s choice for her marriage. Chana and Sumer lived first in Rudnik, a small town in southern Poland. She bore three children by the time World War I destroyed Rudnik. Sumer and Chana, then penniless, moved to Tarnow. They struggled and starved for a while until Chana took on the role of breadwinner starting a business with a good size flourmill. Chana had a fourth child, a boy, who died of illness. To fill the void caused by his passing, “My parents decided to have another baby. That child was me.” William grew up in the provincial town of Tarnow. His family lived in the lower middle class section of the city in an old one-story, seven-family house with no electricity and outdoor toilet facilities shared with six other families.

As the “clouds gathered” in Poland (refer to Chapter 3), William’s maternal uncles, David and Max who lived in America wanted to send visas for the family to come. But William’s father wouldn’t hear of it. Chana wanted to go but his father’s consent was necessary for the family to emigrate. In January of 1930 another child was born—Brandaly, a girl whose name was Polonized to Bronka. It was a time of rising anti-Semitism, deepening economic hardship and poverty. William’s older brother, Natan started his own business at the age of 12 to help the family. He started collecting and selling scraps of cloth from the cutting of garments. He made a profit. This early introduction into the garment industry later help saved his life and the life of his brother, William. William joined a Zionist youth group, went to youth camp and became Bar Mitvahed when he turned 13.

School was where William “felt the change in Polish attitudes toward Jews” the most (refer to Chapter 4, “The Christ Killers). He suffered persecution and anti-Semitism in school from the “Endeks,” a fascist, Polish youth group who taunted Jewish students with slurs of “Christ killers” and threats of violence. Although William and Bronka excelled at school, public high school as well as universities were either impossible to get in because of quotas, or they had just a token Jewish presence where Jews were forced to sit separately and were often beaten. Despite these obstacles, William begged his mother to send him to high school. He attended the newly opened Business High School, the Einspruchowa, a private owned school that only took Jewish students. This school was outside the Jewish quarter. Nevertheless, William went there despite the frequent harassment and beatings from the Endeks. Meanwhile, William’s older sister received a visa from her husband, Simon, and she joined him in Palestine in 1936. William’s older brother, Natan had prospered in the clothing manufacturing business. Since the age of 15, he had been subscribing to American and German trade journals, and he was working for a clothing manufacturer in Tarnow. Despite Natan’s budding prosperity, “the harbingers of disaster were all around us.” By 1938, William was 16 and had an memorable encounter with a Polish cleric who wanted to convert him.

By the late 1930s, news from Germany came to Poland about places like Dachau and Buchenwald and then Kristallnacht (refer to Chapter 5). Exiles from Germany streamed into Poland. William describes in his memoir when the first Germans hit Tarnow on September 8, 1939. “One of the first blows was the murder of the Jewish intellectuals as well as members of the Jewish Kehilla.” In place came the Judenrat and the OD (Ordnungs Dienst), Jewish collaborators chosen by the SS to run the daily affairs of the Jews. “Ultimately they became an instrument and accessory to the liquidation of all the Jews in Tarnow. In this chapter William describes the daily forced labor in a nearby camp, Pustkow, as well as news of Nazi atrocities there. With the advance of the Nazi forces, many Jews tried to escape to the Russian border. On September 17, 1939, the Soviets invaded Poland. Poland was divided in secret agreement between Germany and Poland. Tarnow was in the German side.

The idea of a ghetto became stronger with the new orders that all Jews in Tarnow must move out of their apartments if they happened to be located outside the Jewish perimeter (Refer to Chapter 6, “Ghetto Life”). William and Natan packed to leave, “but our parent’s sad faces deterred us. We decided to stay with them, whatever fate would bring our way.” Jews and gentiles were to be completely separated and forbidden contact. Gentiles were relocated into the evacuated Jewish apartments. This frightened everyone because contact with Polish gentiles was “indispensible to our survival” for “they were the source of food.” William recalls “some resistance was kept alive by Hashomer Hatzair, an underground Zionist group. By October 1939, all Jews in Tarnow and German Poland had to wear the blue star of David arm bands and Jewish men were assigned forced labor in the city. Every week new arrivals were brought into the ghetto, and as William recalls, “not just people from our vicinity.” The existing population before the war was approximately 25,000, “and even with the frequent killings and runaways, the population in our small quarter swelled to over 40,000.” During this time, William had to push coal cars. The Nuremberg Laws were put into effect, Jewish businesses were confiscated, Orthodox Jews were beaten and harassed by SS guards on the streets, and random murders and atrocities occurred on Freedom Square in Tarnow. Nevertheless, Natan had become a skilled craftsman and was able to get a job with a German clothing manufacturer named Madritsch. Eventually, Natan got William a job there too. According to William, “These jobs became instrumental in our long-term survival.” In the short run, the jobs enabled the brothers to return to the ghetto with food for their family. After Pearl Harbor, with the Americans in the war, “our situation took a sharp turn for the worse.” The killing of Jews, which had been sporadic were accelerated and our meager food rations went down. Natan and William continued to work under heavy guard. Round-ups of Jews began and on April 2, 1942, 56 Jews were rounded up in Tarnow and shot for no reason. William states, “This killing was pare of the pattern of steadily increasing terror since June 1941.”

By June 10, 1942, registration and selection for deportation from the ghetto began. William and Natan managed to escape deportation because they worked for Madritsch, providing uniforms for the German Armed forces. In Chapter 6, “Ghetto Life,” William describes in detail the brutality of the selection process. “June 14 turned out to be Hell revisited for the ghetto of Tarnow.” Three thousand people were taken outside the city where a Polish work detail had prepared mass graves. Again, three thousand individuals were loaded like cattle and shipped to Belzec. William describes atrocities to school children and babies in this chapter that are hard to fathom. By the end of this period, 21,000 Jews were “missing;” 12,000 Tarnow natives. “We lived in a state of numbness.” Up to this point, William’s family was relatively spared. They had lost father in the selection process, “but his age meant his loss was inevitable.” Through Natan’s quick thinking, William’s mother and his sister, Bronka, were still alive and they had their jobs and apartment in the ghetto.

But not for long (Refer to Chapter 7 “Mother and Sister”). Chana had two heart attacks and passed. All were distraught, but especially Bronka, only 12 at the time. She had known only suffering her whole short life. Escape was what the brothers wanted for Bronka who was a prime candidate for selection. Frantically, they tried to smuggle her out of the ghetto to a safe house to no avail. On September 12, 1942 they were bull-horned to assemble at Freedom Square for selection. Bronka was selected to go left. Natan tried to follow her to the left, but he was ordered back. The SS would not grant Natan this “favor.” William was sent to the right. Just as Bronka was pushed onto the train, she managed to yell out:

Tell my brothers not to despair. They must not commit suicide! They are still young! They must live to tell our story.

(A witness to this event who was spared by the Nazis delivered this story to the brothers the next day) The brothers never heard from Bronka again.

“Sometime around November 15, 1942, William’s brother Simon joined them. They had not heard from him since September 1939. Simon had been working with a Jewish prisoner work commando for a German company discharging military contracts. He heard his brothers were alive, and at great risk, jumped from work off a transport truck, eluded capture and reunited with William and Natan in the Tarnow ghetto. By August 1943, the ghetto area of Tarnow had been reclassified as “Concentration Camp Tarnow,” so the three brothers were “officially” in a concentration camp under the command of the notorious sadist, Amon Goeth from Plaszow. By this time, only 12,000 Jews remained in Tarnow. Machine guns surround the perimeter. Goeth’s first order was to liquidate 8,000 Jews from the Tarnow. All those who worked for Madritsch which included the three brothers went to a separate selection.

By September 2, 1943, the second selection liquidated the Tarnow ghetto and the brothers headed in a cattle train to Plaszow (refer to Chapter 9, Plaszow). At that time Plaszow was described as a “work camp.” William describes the arrival, the barracks, and the work detail. They survived the brutality and the starvation by working for Madritsch producing military uniforms. In August 1944, William describes hearing rumbling like artillery in the still of the night. Suddenly, evacuation orders were announced by the O.D. The brothers and Madritsch and many others were rounded up and chased to the cattle trains, 150 to a car. The temperature was boiling and there was no water to drink. They travelled for hours and then stopped for two days at the outskirts of Auschwitz “enduring unbearable thirst.”

According to William, “It’s hard to tell time in a boxcar. We must have sat there for two days (Refer to Chapter 10 “Mauthausen”). “The ovens of Auschwitz were working to capacity” and couldn’t take them. The order was to take them elsewhere. They arrived in Austria 72 hours later at Mauthausen, “our third camp. It was our first glimpse, and smell, of a crematorium. Our days were a page from Dante’s Inferno.” We slept 2,000 to a barrack meant for 300. In this camp there was no escape for William or Natan from the brutality of hard labor in the notorious quarry. Eventually, they were sent to labor in St. Valentin, a satellite of Mauthausen. William’s job was drilling holes in tank components. At one point the Nazis called for a skilled watchmaker. William’s brother Simon volunteered. He was put to work on intricate components in tanks, sharing his bounty of solid food with his brothers. Late in their stay at St. Valentin, the Allies began to bomb the camp.

With the relentless American raids, in late April 1945, they were rounded up and loaded on cattle trains once again for transfer to another camp—Concentration Camp Ebensee, the 5th camp for William and Natan (Refer to Chapter 11, “Liberation”). For Simon it was actually his 6th camp. This camp was an absolute Hell as “our bodies had lost what little strength was left, and we were sinking into the abyss.” William and Natan could barely walk. “We were “musselmen, shuffling our feet.” On May 6, 1945 the American Army liberated the camp. The Americans set up a clinic and exams all the inmates. “I weighed 73 pounds.” “Good thing you were liberated” said the Army doctor, “you had two days to live.” Upon liberation, William was miraculously not terribly sick, “just horribly emaciated. Once I started to eat, I bounced back quickly.”

Chapter 12, “Tarnow Revisited” describes William’s travails trying to return to Tarnow to find survivors. “What I really wanted was to go home, to Poland, to see if any of my friends and relatives had survived.” He returns via the United Nations Relief Agency that organized caravans of buses headed for Poland. William describes encountering the Polish home Army which had not disbanded and were still Jew-hunting. Tarnow was a ghost town when William entered it. There was a small Jewish committee in the town offering assistance subsidized by the American Joint Jewish Committee. But William and Natan accepted no assistance. They visited the old Jewish section of town where there was very little standing. They met a few friends and neighbors they knew and shared survivor stories. An attempt to reclaim some of the mechandise that Natan had hidden before his business was confiscated failed due to the confiscation of all the goods and the Polish mobs that harassed returning Jews with anti-Semitic threats and violence. William made his way by hitchhiking and horse-drawn wagon to Grybow, where his brother Simon was living. There he met the few survivors he knew from the region and heard reports from them about the atrocities and murders committed by Amon Geoth of Jews at Plaszow. “Finally it became apparent to me that my future was not in Tarnow.”

Chapter 13, entitled “Odyssey” is just that: the odyssey of William and his brothers newly liberated in their efforts to find their missing family, a home and safety in post war Poland. Simon had already left to take a job as a watchmaker in Katowice. William decided to enroll in a University in Innsbruck, Austria that he heard of that was admitting Holocaust survivors. The military truck transporting William collided with a Russian military vehicle causing serious head injuries, surgery and hospitalization and recuperation. After three weeks in the hospital, William and his brothers, Natan and Simon decided to travel and settle in Wroclaw (formerly Breslau) in lower Silesia. The Polish authorities had forcibly evacuated millions of Germans from the territory, and they moved into one of the vacant flats. The brothers experienced progrom-like round ups, harassment, and anti-Semitism and lock-ups during this period until they finally got released and made their way through various Displaced Persons Camps trying to get to the American Zone. Ultimately, the William entered the American Zone by train, with forged papers travelling with others posing as poor German refugees. He travelled to Munich where the Jews in the group were taken to a camp named Funk Kasserne. Several days later, Simon showed up. By the time Simon arrived, William had signed up to go to a DP Camp in Bavaria called Poking. Simon stayed in Munich.

For a number of weeks Natan knew nothing of his brother’s whereabouts. Finally they were able to contact each other about their location—Munich. Three months after William left Wroclaw, Natan decided to join his brothers in Germany. William writes, “It felt good to be out of Poland, the gravesite of so many Jews (Refer to Chapter 14, “America”). There was a great deal of ambivalence for the brothers. Where to go? America or Palestine? “After the ghetto and the camps, we needed stability, a place to rest our aching bones and live in peace.” William underwent a period of recuperation—16 days—in a hospital in Munich. He entered Munich University but it was difficult to study. He had depression since liberation from Ebensee. Munich was filled with anti-Semitism. The brothers decided to emigrate from Germany to the United States. Relatives, Uncles Max and David in the States sent affidavits. In December 1947, they left by train to Hamburg, where they boarded the Marine Tiger, a former troop ship. “Accomodations were Spartan, but who cared. We were on our way to the Golden Land’” Uncles David and Max greeted them upon arrival and Aunt Clara proposed they board with her in Brooklyn. They hardly had gotten to America when they went to a “Landsmenshaft” meeting—a gathering of people from Tarnow who were living in America. Simon got a job quickly at Longines as a watchmaker. Natan found employment in the garment district as a cutter. William was urged by his brothers to return to college but he was too proud, and instead, took a series of low paying jobs in the garment district. Through his brothers, William was introduced to an 18 year-old girl, a child survivor of the Holocaust, living in the area. Although he was eight years her senior, Edith and William were immediately attracted to each other, and continued dating from their first meeting.

Edith and William became engaged in December 1948 (Refer to Chapter 16, “The Americans”). They were married on September 18, 1948. Edith kept working in the grocery store and then she took a job in Manhattan working for a Textile Corporation as a wholesaler. William was so happy at this time except for his nights which were visited by “terrible nightmares.” His brothers shared his problem, “especially Natan who is still depressed because of his Holocaust experiences.” At first William tried to write about his experiences, but “reliving the horrible experiences didn’t have a healing effect on me. In fact, it magnified the nightmares.” In August 1951, their first child, Renee was born. Their apartment in Flatbush was too small, and William’s commute to his job in Newark—Peter Pan Brasseries—was too long. William decided to change his lifestyle from city to country living. Edith and William decided to buy a poultry farm in Jackson Township, New Jersey. Farming life appealed to Edith. By 1954, William took a leave from his job to build his farm on his newly purchased 10 acres with the help of Uncle Max, who had a farm nearby. On July 25, 1955 Edith gave birth to their second child, a son, Philip. William’s sister, Klara and her husband, Simon moved from Israel to New Jersey in 1956. Simon married a Vienesse woman and settle in Brooklyn, living a “normal life.”

In 1960 at the age of 38, William suffered a stroke. Natan quit his job in Clifton to help with the farm. Natan helped William save the farm during his recuperation. Natan moved into the house that had previously been occupied by uncle Max. In the spring of 1980, Edith and William visited Israel (refer to chapter 17). William concludes, “My first trip to Israel will forever be the highlight of my life.”

In Chapter 18, “My Debt to Bronka,” William outlines the many factors leading to his decision to finally write his memoir: his debt to Bronka, his sister; Edith’s cancer; the sudden death of his brother Simon in 1982 at the age of 71 pointed to him that “life is short and I had better get busy.” The catalyst for William came early in 1983 when a Holocaust exhibit came to a synagogue in Lakewood, New Jersey. William offered to help and he soon became actively involved for the first time in “Holocaust-related-activities,” something he had been avoiding as “too painful a chapter in his life.” His next step was speaking out on a regular basis to high schools and colleges. In 1986, Lisa, William’s daughter-in-law gave birth to Jeffrey, Edith and William’s first grandchild. In 1987 William retired from the poultry business. In 1989 William and Edith celebrated their 40 wedding anniversary. William ends chapter 18, “Ever since I was a child, I had a great love of writing…I have made the decision to put down the highs and the lows of my troubled life on paper, at least as a testimony for my family. Edith convinced me to go ahead, who else?”

Editor’s Note:

Refer to Historical Notes Below for Tarnow Ghetto, Amon Goth and Final Deportation

-

SURVIVOR INTERVIEW:

Refer to William Kornbluth’s Biography above adapted from Sentenced to Remember .

-

HISTORICAL NOTES:

TARNOW GHETTO, AMON GOTH AND FINAL DEPORTATION-SEPTEMBER 1943

During the summer of 1943, there were still about 9,000 Jews in the Tarnow Ghetto, the Ghetto was divided into two sections “A” and “B.” Section “A” accommodated Jewish men, women and children aged 12 years and above, all of whom were organised into working squads who paraded daily in columns to march to their work sites inside and outside the ghetto.

This section of the Ghetto had the official name: “Forced Labour Camp T.” Section “B” accommodated Jews of both sexes and of all ages who were unfit for work, including children below the age of 12 years.

Both sections were separated by a wooden partition. Inmates of one section were not permitted to enter the other section. The Ghetto measured 1km long and 200m wide and was surrounded by a wooden fence of 2m high. Contact between the male area and the female area within the Ghetto Section “A” was also strictly prohibited. Jews violating this directive were shot by the Gestap

During the middle of August 1943, a conference was held in the office of SS-Obergruppenfuhrer Friedrich Kruger in Krakow with SS-Oberfuhrer Scherner presiding. Also in attendance Chief of the Tarnow Gestapo Palten and SS chiefs Bernhard and Blache, they learned that a fourth aktion would take place in early September 1943, and that it was designed to deport the remaining Jews.

A sinister appointment was made by Schener in the appointment of Amon Leopold Göth the commander of the Krakau-Plaszow Forced Labour camp. Göth served with Globocnik as a member of Aktion Reinhard, and liquidated the Krakow Ghetto and a number of other ghettos in Poland.

At the end of August 1943, a further conference was held to fine-tune the fourth and final action in Tarnow. The details of the intended operation were established.

According to the details 200 Jewish males and 100 Jewish females were to remain in the ghetto to serve as a clear-up party. 2,000 Jews from the Madritsch clothing factory were to be transferred to Krakau – Plaszow Forced Labour Camp.

When the Krakow Ghetto was liquidated on the 13 March 1943 Julius Madritsch transferred 232 men, women and children from Krakow to Tarnow. This took place on the 25 and 26 March 1943.

On the 3 September 1943 the Ghetto in Tarnow came to a brutal and violent end. The day before the liquidation Madritsch and Raimund Titsch were invited to a ceremonial dinner for Commandant Göth and other high SS officials. When Madritsch requested to leave the dinner, Scherner ordered him to stay until dawn and left him with two SS officers to keep them company.

At 5am the following Madritsch and Titsch were released, they drove directly to Tarnow where they saw Göth. Göth informed them that the Tarnow Ghetto had been liquidated but assured Madritsch that his workers were safe for the time being.

Large bribes were not offered, but demanded by Göth and Scherner. Madritsch had observed that there had been a fierce resistance in the Ghetto and many Jews had been shot. All the Jews who survived the onslaught in Tarnow Ghetto were transported to Auschwitz – Birkenau. Only the Jewish workers at the Madritsch works survived.

MAUTHAUSEN AND EBENSEE CONCENTRATION CAMPS

The construction of the Ebensee subcamp began late in 1943, and the first 1,000 prisoners arrived on November 18, 1943, from the main camp of Mauthausen and its subcamps. The main purpose of Ebensee was to provide slave labor for the construction of enormous underground tunnels in which armament works were to be housed. These tunnels were planned for the evacuated Peenemünde V-2 rocket development but, on July 6, 1944, Hitler ordered the complex converted to a tank-gear factory.[2]

Approximately 20,000 inmates were worked to death constructing giant tunnels in the surrounding mountains. Together with the Mauthausen subcamp of Gusen, Ebensee is considered one of the most horrific Nazi concentration camps.

Jews formed about one-third of the inmates, the percentage increasing to 40% by the end of the war, and were the worst treated, though all inmates suffered great hardships. The other inmates included Russians, Poles, Czechoslovaks, and Romani, as well as German and Austrian political prisoners and criminals.

The Commandant Otto Riemer (born May 19, 1897, date of death unknown) was a Nazi, a crew member of the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp, and SS-Obersturmführer. Unfortunately, his fate is unknown.[3] Another SS man was Alfons Bentele, who died in a French prison.

Inmates of Ebensee concentration camp after their liberation by American troops on May 6, 1945 (Photograph by Arnold E. Samuelson).

Prisoners arose at 4:30 a.m. and worked until 6:00 p.m., constructing and expanding the tunnels. After some months the work was done in shifts covering 24 hours a day. There was almost no accommodation to protect the first batch of prisoners from the cold Austrian winter and deaths increased greatly. Bodies were piled in heaps and taken every three or four days to the Mauthausen crematorium to be burned, as Ebensee did not then have its own crematorium. The bodies of the dead were also piled inside the few huts that existed. The smell of the dead combined with the stenches of sickness, phlegm, urine, and faeces was said to be unbearable.

Prisoners wore wooden clogs, and went barefoot when the clogs fell apart. Lice infested the camp. In the morning, food rations consisted of half a liter of ersatz coffee; at noon, three quarters of a liter of hot water containing potato peelings; and, in the evening, 150 grams of bread. Due to such inadequate rations and the inhuman living conditions, beatings, and the onerous demands of the hard labor, the death toll continued to rise.

-

Sources and Credits:

Credits:

William Kornbluth, Sentenced to Remember: My Legacy of Life in Pre-1939 Poland and 68 Months of Nazi Occupation (Leigh University Press, 1994); Adapted Biography by Nancy Gorrell from Sentenced to Remember.

The SSBJCC Holocaust Memorial and Education Center gratefully acknowleges the donation of hardcover copies of Sentenced to Remember donated by Phil Kornbluth and digital historic and family photographs and documents therein. The Center also gratefully acknowledges the donation of a digital copy of Sentenced to Remember by Phil Kornbluth.