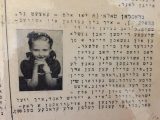

- Local Survivor registry

- TOVA FRIEDMAN

- Local Survivor registry

- TOVA FRIEDMAN

Survivor Profile

TOVA

FRIEDMAN

(1938 - PRESENT)

PRE-WAR NAME:

TOLA GROSSMAN

TOLA GROSSMAN

PLACE OF BIRTH:

GDYNIA, POLAND

GDYNIA, POLAND

DATE OF BIRTH:

SEPTEMBER 7, 1938

SEPTEMBER 7, 1938

LOCATION(s) BEFORE THE WAR:

TOMASZOW, POLAND

TOMASZOW, POLAND

LOCATION(s) DURING THE WAR:

TOMASZOW, MAZOWIECKI (GHETTO); STARACHOWICE, POLAND CONCENTRATION CAMP, POLAND (SPRING 1943); AUSCHWITZ II -BIRKENAU (DEATH CAMP); KINDERLAGER (JUNE 1944).

TOMASZOW, MAZOWIECKI (GHETTO); STARACHOWICE, POLAND CONCENTRATION CAMP, POLAND (SPRING 1943); AUSCHWITZ II -BIRKENAU (DEATH CAMP); KINDERLAGER (JUNE 1944).

STATUS:

CHILD SURVIVOR

CHILD SURVIVOR

RELATED PERSON(S):

MAIER FRIEDMAN - Spouse (Deceased),

RISA FRIEDMAN - Daughter,

SHANI FRIEDMAN - Son,

ITAYA FRIEDMAN - Daughter,

GADI FRIEDMAN - Son,

MACHEL GROSSMAN - Father (Deceased),

RAIZL GROSSMAN - Mother (Deceased)

-

extended BIOGRAPHY By ADAPTED NANCY GORRELL

FROM KINDERLAGER: AN ORAL HISTORY OF YOUNG HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS (BOOK 1, TOVA) BY MILTON NIEUWSMA

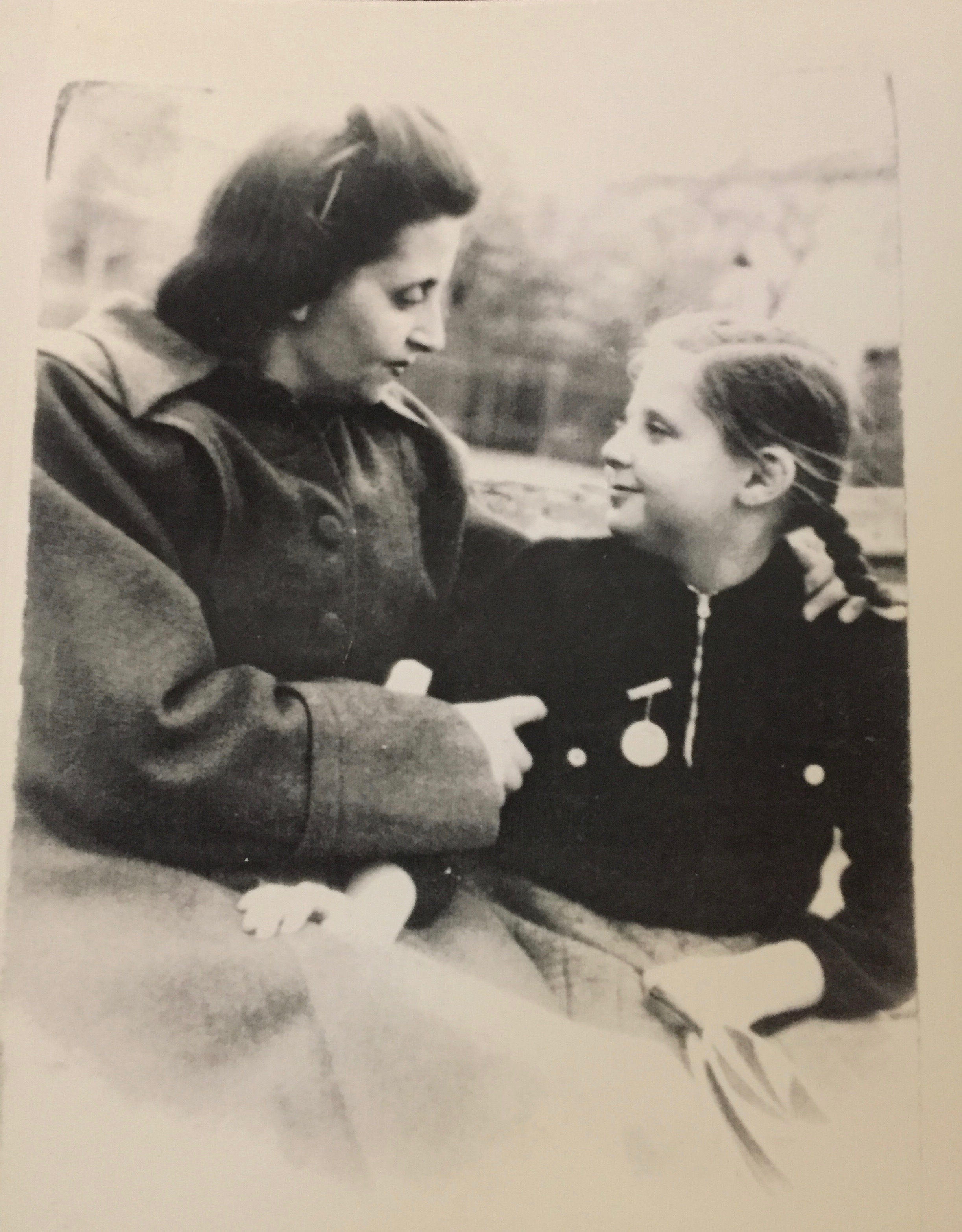

Tova (Tola) Grossman was born September 7, 1938 to Machel and Raizl (Rose) Grossman, in a town called Gdynia, on the outskirts of Danzig on the Baltic Sea. Her father, a Zionist, opened a clothing store with his brother. Her mother, Raizl Pinkushewitz came from a family of scholars and rabbis and spent most of her time taking care of Tova, her only child. Tova considers her parents and herself among the “lucky ones”—they all survived the Holocaust. Two weeks before the war broke out, her mother had a premonition. She fled with her baby to Tomaszow, the town where both she and Tova’s father grew up, to Tova’s grandparent’s house.

Then on September 1, 1939 the Nazis invaded Poland. Tova’s father’s store in Danzig was destroyed and her uncle killed. Later Tova describes the Gestapo forcing her family out of her grandparent’s house and into the ghetto with other Jews. In Milton Nieuwsma’s work, Kinderlager: An Oral History of Young Holocaust Survivors, Tova describes the process: first it was “Jews not allowed,” confiscation of Jewish property, and after that the ghettos and labor camps. Last came the death camps. In spring of 1943 the Gestapo came at night and took Tova and her parents on a truck to a labor camp—Starachowice. It was there that Tova spent her early childhood learning from her mother how to stay alive. Her mother taught her the “rules” of survival: “First, if you see an SS person coming toward you, step off the sidewalk. Second, don’t ever look into the eyes of an SS person. Third, if you’re wearing a hat, take it off.” Tova’s parents were gone all day working in the munitions factory while Tova, alone with the other children, “ran around like street urchins, eating from garbage cans and shooting each other with sticks playing ‘I’m the Nazi, you’re the Jew.’” Later Tova describes the SS starting their roundups, shootings and selections for deportation. From then on she had to stay inside, hiding all day alone from the guards. Still she was with her parents. A month later, June 1944, the Germans closed the labor camp, and Tova and her parents were rounded up for deportation. At the train, she and her mother were separated from her father. The trip took three horrific days, but she was with her mother. When they arrived, she saw her father only to learn he was going on to Dachau. Tova was the only child. She was still with her mother and the women. They were all stripped naked, shaved together and taken to three tier bunks. Tova describes the dreaded Appell, the lining up and counting of names, the persistent hunger and getting scarlet fever. She was only five years old, barely surviving in the women’s camp, but she was with her mother who told her everything and what to do. Tova survived.

At the end of July 1944, the Germans liquidated the Gypsy camp at Auschwitz; the remaining children were transferred there to a section they called, Kinderlager. Tova recalls her mother crying at their separation a few hundred yards away. She also recalls the “woman with the needle” tattooing her arm with her number: A-27633. Then she said, “Memorize your number, you no longer have a name.” Tova recalls that the real war began for her in the Kinderlager. She was completely alone, without Mama or Papa to protect her, and she was the youngest (most were teenagers) and by far the smallest. The teenagers were talking about Mengele and what he was doing in the camp nearby. Tova describes children dying of starvation all around her—the Muselmann—as the Germans referred to them because of their prayer-like posture. Remarkably, when Tova turned six, her mother smuggled some bread to her for her birthday. Other miracles happened as well. Tova describes marching to the crematorium with the other children, getting towels and getting undress, only to hear guards arguing, “Wrong block, send them back!” One day her mother showed up at the Kinderlager. “They’re sending us on a march…let’s try to hide.” Once again Tova’s mother saved her. They hid together in the camp hospital. One week later, they were liberated by the Russian army. Tova recalls the ensuing chaos of those days and travelling with her mother back to her grandparent’s house in Tomaszow. They found the home, and eventually, reunited with three of her father’s eight siblings. Tova and her mother moved into the cellar of that house with her father’s three surviving sisters. They waited for others to return. No one did.

Tova recalls the post-war anti-Semitic slurs and atrocities she was subjected to in the fall of 1946 as a child in a Polish classroom: “You dirty Jew! Why are you alive?” Every day she prayed to see her father. Her mother taught her how to count. She counted 1000 days since she last saw him. She kept counting. Then there came a knock at the door. The three of them were reunited at last only to learn from Papa that aunt Helen had been murdered in a Lodz jewelry store. Papa moved the family and aunt Elka to Berlin where they lived in the American zone. Before they could go to a DP camp, they needed a physical first. The doctor discovered Tova had TB, and so she was sent to a sanitorium in southern Germany. At the age of 8 ½ she was on her own again. She was there for a year, finally recovered and was reunited with her parents at a DP camp in Landsburg, Germany. The year was 1948. Papa debated whether to go to America or Israel.

On April 4, 1950, Tova arrived in New York City with her parents. Her father found work as a tailor, and they moved to Queens. In 1952 the family moved to Brooklyn. Tova joined a Zionist group, Habonim, and at eighteen, started Brooklyn College. In 1957, Tova decided to go to Israel. While she was away, her mother died suddenly of an aneurysm (June 29, 1957). Tova was filled with grief; her father blamed her. Tova moved into a boardinghouse in Brooklyn, the Girls Club. She lived there for the next three years, receiving counseling from Dr. Lillian Kaplan, a psychiatrist who treated Holocaust survivors. In 1960 she graduated from Brooklyn College with a major in psychology. Tova married Maier Friedman, the boy she knew from Hebrew school on June 11, 1960, a week after she graduated. She was 21; he 22. In April 1967 after they had two children, and Maier had his Ph.D and Tova her Masters, they left America for their beloved Israel. Tova describes her “euphoria” after landing in Israel and going the next day to Jerusalem. “Instead of marching with the children to the crematorium, I was walking with my family toward the Wall. I felt at peace and at home.” Tova’s third and fourth children were born in Jerusalem in 1969 and 1975. In 1977 Tova and her family moved back to the United States. Her father died in 1983. After the founding of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Tova was notified she was the youngest survivor of Auschwitz. That is how she became part of Milton J. Nieuwsma’s research.

Tova and her family are featured in two documentaries directed by Raritan Harry Hillard, The Other and The Second Generation: Ripples From the Holocaust, as well as Surviving Auschwitz. Tova, one of the youngest survivors of Auschwitz, was part of a reunion of child survivors of the Auschwitz concentration camp that was featured during a segment of NBC Nightly News with Lester Holt (June 5, 201

Tova’s Legacy:

I always thought I should have had six children, one for every million Jews killed in the Holocaust to help replenish the lives that were lost. But I stopped at four…. Mama once told me, “I don’t have much to give you, but one thing I want you to know is you have to trust, respect, and love yourself. If you don’t, no one will.” I was only 12 or 13 then, but I always remember that.

Did God save me for a purpose? I don’t know…but since I did survive, I can’t just go about business as usual. More than anything, I want Mama to know that despite the pain, I’m going on with my life and trying to make a difference.

Tova and her family are featured in two documentaries directed by Harry Hillard, The Other and The Second Generation: Ripples From the Holocaust, as well as Surviving Auschwitz.

Tova, one of the youngest survivors of Auschwitz, was part of a reunion of child survivors of the Auschwitz concentration camp that was featured during a June 5, 2017 segment of NBC Nightly News with Lester Holt: “72 Years Later, a Reunion for 3 Survivors seen in Iconic Holocaust Image.” (Refer to the photograph in Related Media). Reference the following link for video:

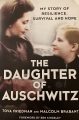

Tova’s Life Memoir is Published (2022)

The Daughter of Auschwitz: My Story of Resilience, Survival and Hope

The book is available on Amazon. See book cover in Related Media.

TOVATOK: Social Media Interviews with Grandson, Aron Goodman

Tova has produced with her grandson, Aron Goodman, interviews of her story to combat hatred, Holocaust denial and anti-semitism.

Editor’s Notes:

(Refer to the photograph in Related Media of ” 72 Years Later Reunion of Auschwitz survivors” by Lester Holtz. Refer to the following link for video:

Refer to grandson, Aron Goodman in Voices of the Descendants.

Refer to daughter, Taya Friedman in Voices of the Descendants.

Refer to Historical Notes Below on Auschwitz-Birkenau

Refer to Related Textual Material Below for selected chapters of Tova’s story in Kinderlarger.

-

SURVIVOR INTERVIEW:

INTERVIEW WITH TOVA FRIEDMAN

Date: July 21, 2017

Location: Jewish Family Service Office, Somerville, New Jersey

Interviewer: Nancy Gorrell

Topic: Post-War Interview about the Period after Liberation

Q: Describe what happen to you after liberation.

After liberation, we stayed in Auschwitz for three months. The first thing my mother did was not to let me eat. First I ate dried bread. The second day I had bread and butter to get used to fat. The third day she gave me bread, butter and sugar to get used to sweet. She showed me the people dying of diarrhea from what the Russian army gave them (rich foods). She decided to tell me to remember all of this. And then she took me to a place where there was soap, and she said this was soap made out of human fat. She asked, “Should we take this back? Look to the shades? This is what they did to us.” I don’t know why she did that. She really treated me like an adult. We lived with the other refugees liberated and the Russians gave us blankets and old clothing. All I can remember is terrible chaos in the barracks. We didn’t understand what they were saying, where we were going, or what part of Poland we were in.Q: When did you leave Auschwitz?

After a few months, the American Red Cross came, and they gave us a paper document so if we leave the camps, we could show authorities we were from the camps. My mother again took me to the storage places where there were valuables. She wanted me to be a witness. She always shared everything with me. In one of the places she took a man’s coat; she took a very big coat and took the bottom off and wrapped herself in it. She wrapped me in what she could find. And that’s how we walked out of Auschwitz, with my mother wearing a very long coat, and me bundled me up and the paper. We went to Tomaszow, Poland where the family lived for 200 years. We went back to my hometown to see if anybody returned with my mother.Q: What was it like seeing your hometown?

The first thing when we entered the city, a woman came towards us that was a neighbor, calling at us, “What are you doing back here? I thought that Hitler killed you all.” We walked the streets and everything was ruined where my mother and grandparents lived before the war. We walked from one ruin to the other. That was before the Jewish community organized anything—we had nowhere to sleep and nothing to eat. My mother found an open cellar and my mother said we had no choice. It was an earthen cellar and we found a few sacks and laid down on that. We stayed in that cellar for a few weeks until my father’s three sisters, who were saved, came back. They were Ita, Elka and Helen. They took us out of the cellar and somehow we got a tiny apartment. I don’t know where they got a sewing machine. Slowly people were trickling in, and they began sewing for the Russian army—pants after pant after pants. And the soldiers came. And that’s how we began to eat. Before that, we were almost starving. We ate better in Auschwitz than when we came back to our hometown.Q: Who survived in your family or town?

A total of 300 Jews returned out of 15,000 and a total five children returned out of 5,000. Nobody returned from my mother’s family—not one relative out of 150 extended family members (she had 10 brothers and sisters). And she lived the rest of her life knowing she was the only survivor out of her Hasidic family. The Hasidics were killed first. Her name was Raisl (Rose) Grossman. My mother, when she realized that nobody came back, went into a serious depression, almost a coma-like state. She couldn’t take a train because it reminded her of the cattle-cars.Q: Did your father survive?

Within a year and a half, my father returned from Dachau. It was the same day his sister, Helen was killed. He didn’t know where anyone was and arrived in our hometown much later. When he return, he took over and in 1948, he and his two younger, married sisters, and all of us sneaked into Germany to look for the American army because life in Poland was so tough under the Russians. We went to the American zone and the Displaced Persons camp. My mother looked at me and said “Listen, you have been through terrible things. There are so many wonderful things in the world.” She made me take piano lessons to play Chopin. I gave my piano teacher the canned food we were getting for the lessons. That’s how I developed the love of music. We left in 1950, but before that I spent nine months in a sanitarium for TB recuperation. In April 1950 we arrived in America at Passover time.Tova’s Message to Future Generations:

The most important thing is to be an historical witness. You should let the next generation know so the 6 million and half should not become sand and be forgotten.

-

HISTORICAL NOTES:

Historical Notes: Muselmann and Auschwitz-Birkenau

Muselmann (pl. Muselmänner, the German version of Musulman, meaning Muslim) was a slang term used among captives of World War II Nazi concentration camps to refer to those suffering from a combination of starvation (known also as “hunger disease”) and exhaustion and who were resigned to their impending death.

The Auschwitz complex was divided in three major camps: Auschwitz I main camp or Stammlager; Auschwitz II, or Birkenau, established on October 8th, 1941 as a ‘Vernichtungslager’ (extermination camp); Auschwitz III or Monowitz, established on May 31th, 1942 as an ‘Arbeitslager’ or work camp; also several sub-camps. Auschwitz II included a camp for new arrivals and those to be sent on to labor elsewhere; a Gypsy camp; a family camp; a camp for holding and sorting plundered goods and a women’s camp. In March 1942, a women’s camp is established at Auschwitz with 6,000 inmates. In August 1942, it was moved to Birkenau. By January 1944, 27,000 women were living in Birkenau, in section B1a, in separated quarters. Auschwitz III provided slave labor for a major industrial plant run by I G Farben for producing synthetic rubber. Highest number of inmates, including sub-camps: 155,000. The estimated number of deaths: 2.1 to 2.5 million killed in gas chambers, of whom about 2 million were Jews, and Poles, Gypsies and Soviet POWS. About 330,000 deaths from other causes.

-

related textual material:

KINDERLAGER: AN ORAL HISTORY OF YOUNG HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS (BOOK 1 TOVA)

TOVA, CH. 1: THE CHINK IN THE WALL

TOVA, CH. 2: A NUMBER FOR MY NAME

TOVA, CH. 3: THE CREMATORIUM

TOVA, CH. 4: "CANADA"

TOVA, CH. 5: HELEN

TOVA, CH. 6: MAMA

TOVA, CH. 7: ISRAEL

TOVA, CH. 8: THE LEGACY

-

Sources and Credits:

Credits:

SSBJCC Interview of Tova Friedman July 21, 2017 by Nancy Gorrell ; Digital and historic family photographs donated by Tova and Taya Friedman. Biography by Nancy Gorrell adapted from Kinderlager: An Oral History of Young Holocaust Survivors, Book One, Tova; Milton Nieuwsma, ed. Scholastic Inc.1998.

The SSBJCC Holocaust Memorial and Education Center gratefully acknowledge permission received to reproduce Book One: Tova from Milton J. Nieuwsma ed., 1998, Scholastic Inc. The Center also gratefully acknowledges a copy of the book Kinderlarger donated by Tova Friedman.

Additional links provided by Taya Friedman:

Surviving Auschwitz: Children Of The Shoah; Story 63 of Auschwitz: Tova Friedman (USC Shoah Foundation: Jan 22, 2015); Tova Friedman, Auschwitz Survivor, Part 1 & 2, (Caesar Darias, UTube Feb. 9, 2013); Tova Friedman Holocaust Survivor, (Edison BOE, UTube video, September 9, 2016); Harry Hillard, The Other, Surviving Auschwitz (RVCC).