SECOND GENERATION REMEMBRANCE BY STEVEN FUERST

A Brief History of German Jewish Chicken Farmers in our Region

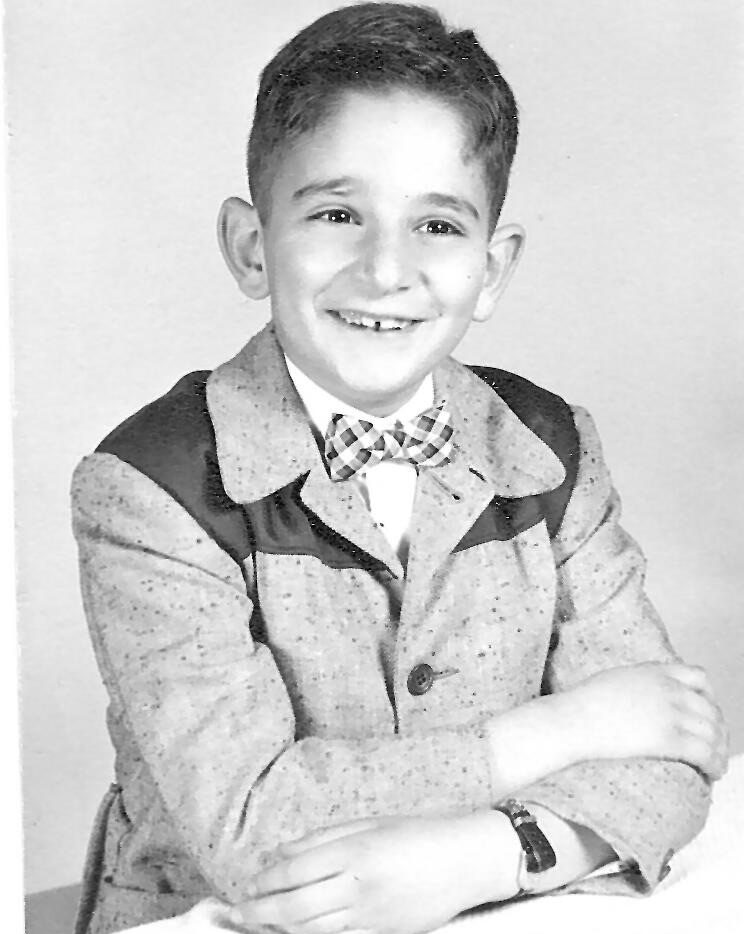

From my earliest days, I remember German being spoken in the home. My mother's mother, Helena Loewengart, lived with us and never learned English. When I went to kindergarten at Somerville Elementary School, I started to stutter because I spoke German at home and English at school. Teachers there recommended that we speak only English in the home, and within weeks my stutter vanished.

At that time in Somerset County, there were quite a few Jewish families who had fled Germany in the 1930s. My father was one of the few who owned a business; most owned chicken farms in Franklin Township, Warren Township, and Hillsborough, where there was a German-Jewish resort across from Duke Farms. A few were related or had known each other in Germany. Most, however, developed relationships through area synagogues in Somerville and Bound Brook or under the auspices of the Jewish Agricultural Society.

The society had been pushing chicken farming as a business for displaced German Jews, many of whom could not find work in America. In Germany they had been doctors, lawyers, chemists and other professionals. Some had been wealthy. What to do in America became a pressing concern. Start-up costs for poultry farming were significantly less than a traditional farm, and the work was not as back- breaking, important since many of the German refugees were in their late 40s and 50s.

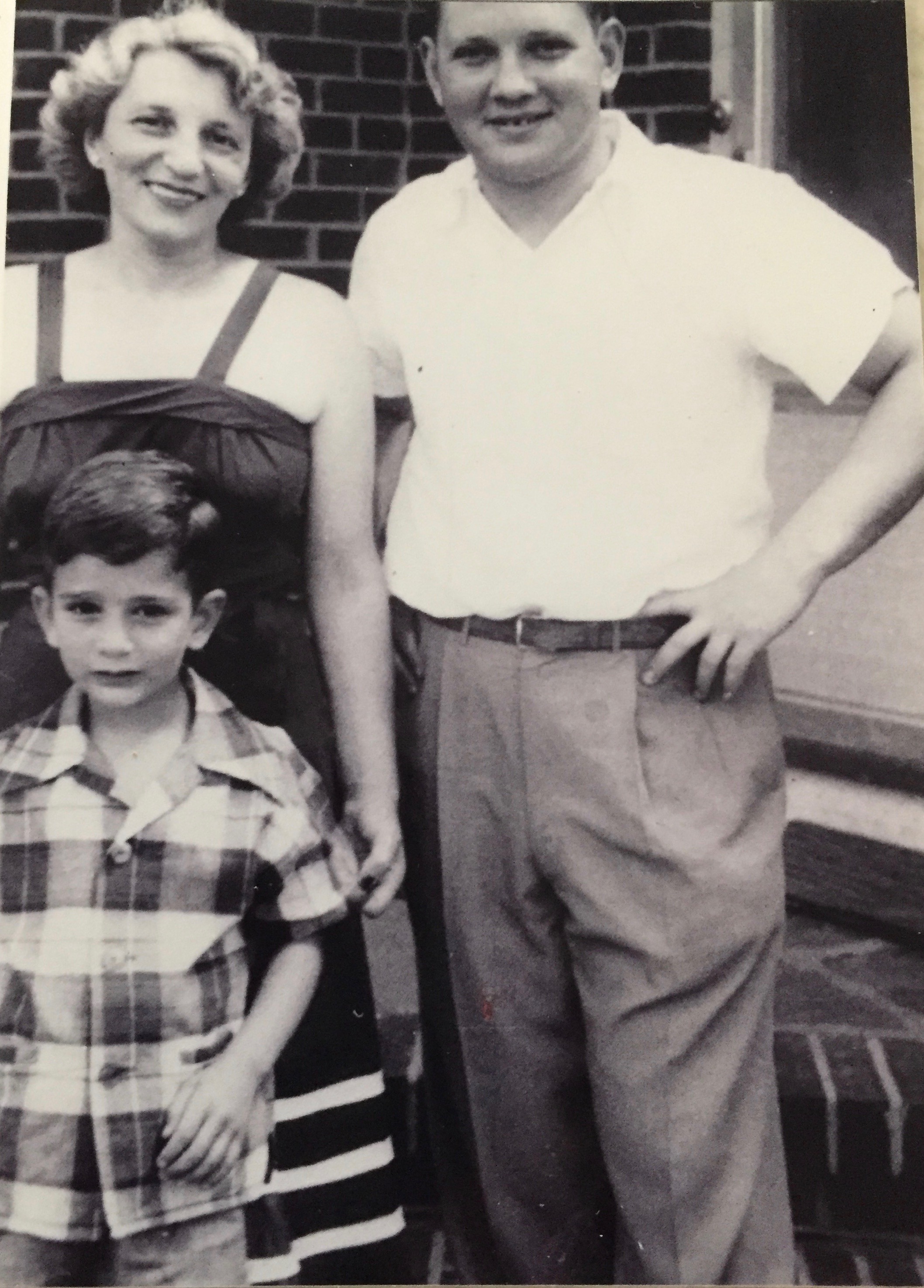

My father owned a feed business in Somerville called Sunrise Milling, and many of the firm's customers in Somerset, Hunterdon, and Middlesex counties were German Jewish farmers. In fact, my father, who was single, was introduced to my mother by her older brother, who had a chicken farm in Franklin.

Since. so many refugees farmed, recreation had to wait until the weekends. I remember countless Saturday afternoons where German friends would get together at our house for coffee and scrumptious cakes prepared by my mother. Naturally, the talk was about Germany

and how wonderful it had been before Hitler.

I knew the children of these refugees, but since we were all American born and had very little understanding of our parents' life in Germany, we hardly discussed those difficult journeys our parents made from Germany to Central New Jersey. However, in the summers from the time I was 15 until a sophomore in college I worked as a waiter at a German Jewish summer resort in Fleischmanns, New York. All of the wait staff as well as the guests were German-Jewish refugees and the good friends I made there had similar backgrounds. Among them were the Daniel brothers, who lived on a farm in Three Bridges, Hunterdon County.

Many of the areas German Jewish farmers struggled financially, but when the building boom of the 1970s hit, they sold their properties and moved away, most to Florida. My uncle Alfred’s and aunt Thea’s farm on Elizabeth Avenue in Franklin was subsumed by the big industrial park off Interstate 287 near Weston Canal Road. Another of my parent’s friends’ farms in Warren today is the site of several large shopping centers on Washington Valley Road.

Doris Duke bought another friend’s farm in Hillsborough, and developers snapped up German Jewish farm properties along Route 206 in Hillsborough and Neshanic. Perhaps the only farm that still exists is my uncle Kurt’s farm on Route 31 in Ringoes.

STEVEN FUERST AND HIS DAUGHTER, EMMA, VISIT REXINGEN TO

LEARN ABOUT THEIR GERMAN JEWISH HERITAGE

Steven, a second generation Holocaust survivor, and Emma, who represents the third generation, traveled to the Black Forest region of Germany to visit Rexingen, the village where Else Fuerst grew up. They were able to visit her childhood residence, the town’s Jewish cemetery, and the synagogue, which villagers helped rescue from the ravages of Kristallnacht and now use as a church. Jews had lived in Rexingen for over 400 years, first arriving in 1516 when the Knights of St. John – a Christian Order dating back to the 11th century – offered them protection.

For centuries, Rexingen’s Jews and Christians lived in peace and harmony. But in the 1930s, a swastika appeared on the four-meter tower that overlooked the village; Nazis paraded through the village, and the Nuremburg laws reared their ugly head. Else Fuerst and her family were able to leave and settle in the United States, but most Rexingen Jews settled in a small moshav near Haifa at the end of 1937. That moshav called itself Shavei Zion (Returnees to Zion).

Steven and Emma have also visited Shavei Zion. Today it is a thriving business, farming, and tourism community.In Shavei Zion the synagogue was meant to resemble Rexingen’s house of worship. Several decades later, Else Fuerst’s family donated money for a community hall whose stunning reliefs were created by German-Israeli sculptor Rolf Roda Reilinger.

On display in its memorial room is a Torah scroll, partially burnt and bearing marks left where it was cut by knives and axes in 1938 on Kristallnacht. The scroll was saved by a Christian policeman who understood that the last of the community would be leaving soon and helped one of the Jews bound for Israel to smuggle it out of Germany. It sits on a wall inscribed with the names of all of the Rexingen residents who didn’t make it to safety in Israel.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Fusce condimentum lacus purus, et suscipit justo semper nec. Maecenas non lectus odio. Aliquam volutpat neque ac placerat gravida. Nullam sit amet venenatis ante. Proin vestibulum volutpat purus vel dapibus.